On 14 February 2024, the UK High Court ruled that the University of Bristol had failed in its duty to make reasonable adjustments for Natasha Abrahart, a 20-year-old physics student with chronic social anxiety disorder. Having repeatedly struggled with the oral assessment component of her degree, Natasha took her own life on 30 April 2018, the day that she was scheduled to offer a presentation to lecturers and her peers in a lecture theatre of over 300 seats. The court upheld the ruling that the university was guilty of discrimination that had contributed to her suicide. The chair of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Baroness Kishwer Falkner, expressed her hope that the High Court ruling would empower disabled students and clarify what they should expect from their universities.

All statistics and examples in this article are taken from a two-year period of research during which I have collated the experiences of disabled university students across the UK. These case studies and feedback have highlighted that the failure to provide reasonable adjustments, when the practicability of these adjustments is clear, is the most common form of discrimination encountered. While many disabled students reported supportive working environments, with the Open University emerging as outstanding, only 40 per cent reported that the lecturers they worked with were aware of the UK government’s 2010 Equality Act. Only 68 per cent of students found that academic staff readily committed to the provision of reasonable adjustments. Of those students who confirmed experiencing discrimination, 72 per cent admitted that they were unsure how to challenge decisions, and an even higher percentage feared retaliation and further discrimination if they turned to other areas of the university for help.

- How to make your university more neurodiverse friendly

- For diverse communities to thrive, we need intersectional policies and practices

- What I’ve learned from a decade of working with a disability in academia

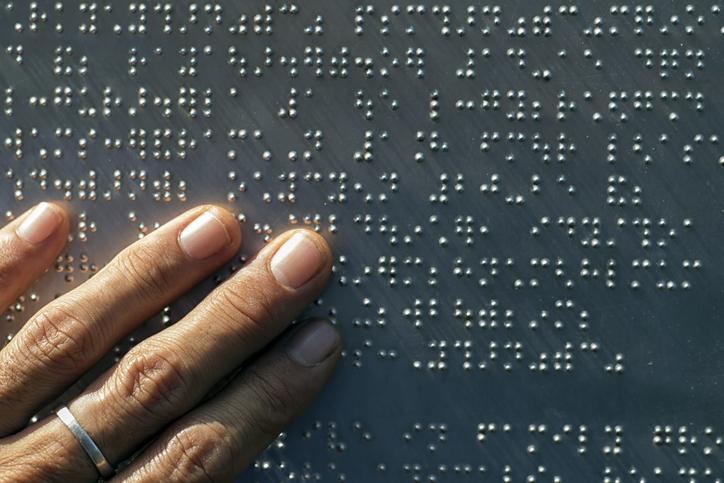

Students with disabilities ranging from sensory impairments and motor neurone disease to dyslexia and mental health diagnoses are making their way through secondary school only to find that their university experiences are unpredictable and often dependent on the attitude and understanding of their lecturers and support staff. Under the government’s Equality Act of 2010, disability is one of nine protected characteristics, and prohibited conducts fall into several categories.

Reasonable adjustments create an environment in which students with special educational needs or disabilities have an equal opportunity to display their intelligence, accomplishments and understanding. This could be extra time allowances for written assessments and exams, alternative means of assessment if oral assessments prove distressing or impossible, seminar rooms or labs with access for wheelchairs, assisted technologies in study areas or altered formats of module reading.

The most common failing reported was time extensions being refused, and the reasons given by lecturers included wanting to mark all assessments at once, going on holiday, the end of term or attending a conference – or the student was pressured to submit at the same time as other students if they wanted the work to be marked. Most of the students in this situation found the struggle to complete work impacted their mental health and, for many, assessments were submitted unfinished. Other case studies included wheelchair users who were unable to access seminar rooms, lecture theatres and offices, when swapping venues would have been both practicable and easy to arrange.

Students struggling with anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress reported being put on the spot in seminars and told to contribute to discussion or their marks for the term would be adversely affected. One young woman struggling with severe social anxiety was told she shouldn’t be discussing her “weakness” with lecturers or her peers after stammering and struggling to deliver a presentation and trying to explain her nerves. Most disabled individuals in my study feared that their marks would suffer if they complained about failings, 23 per cent said they had dropped out or thought this would be the result if the failure to provide reasonable adjustments continued with their degree course.

How to ensure reasonable adjustments are made for disabled students

These situations can be avoided. Lecturers can follow a simple process to guide students with disabilities to the right solutions.

For most students in the UK, reasonable adjustments will be detailed in their assessment for the Disabled Students Allowance.

Alternatively, students can ask the university’s disability officer or adviser to carry out a needs assessment. The disability adviser will then advocate for the student by emailing lecturers to request the adjustments. If these are not forthcoming, the student should then email the lecturer who has failed to comply, detailing the reasonable adjustment they need and why it’s important. They can add a copy of the relevant section of their DSA assessment. The student should ensure they copy in a third party, such as the module leader, disability adviser or a supportive lecturer, and they should keep records.

If the individual approached refuses or ignores the request, the Equality Advisory Support Service (EASS) stipulates that after two weeks, the student should escalate the request using the university’s official complaints procedure. At this point, most requests find a happy resolution. If not, the student can apply to an ombudsman or county court.

The best place to look for a template for any complaint in the UK is the resources section of the EASS website. A subheading under disability deals with further and higher education, and both existing and prospective students are protected under the Equality Act 2010. The Equality and Human Rights Commission website also has a subsection on disability discrimination and the commission’s legal work. Do reassure your student that in the UK complying with the request for reasonable adjustments is a legal obligation.

Kate Armond has taught literature and international modernism at the University of East Anglia and the University of Essex. She is now senior lecturer in literature and critical theory. The research for this article was made possible thanks to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Scope and Mind.

If you’re having suicidal thoughts or feel you need to talk to someone, a free helpline is available around the clock in the UK on 116123, or you can email jo@samaritans.org. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment