Whenever I am told that a blind or partially blind student will be joining one of my courses, I immediately make sure that all the set reading is available in a suitably accessible format. Blind students are extremely good at explaining how they prefer to access texts, and university libraries and disability support offices are usually very efficient in providing materials in audio, Braille, large-print or electronic formats as required.

But access is about much more than reading lists. Here are six suggestions for creating an inclusive learning environment for all students.

1. Make sure everyone knows who is in the room

Non-blind students can gain a lot of information about lecturers’ and students’ identities just by looking at them. But blind students won’t know who is in the room unless they are explicitly told. If your ethnicity, age, gender identity, disability, clothing style or other visually apparent characteristic is an important part of who you are, then it is worth including in a quick audio description of yourself at the beginning of the class. (“I am a white cis-woman in my late forties. I am partially blind and carry a white cane.”) Without this information, there is a real danger that non-visual students will assume that everyone belongs to the white, cis, non-disabled “norm”.

- Diversity statements: what to avoid and what to include

- Seven steps to help students stay engaged online

- Want to tear students from their phones? Learn their names

2. Say your name (and other people’s)

Contrary to popular belief, blind people do not have a magically enhanced sense of hearing, and we do not always recognise people by voice alone. To help all students get to know each other and keep track of who is speaking, say your name before you speak and ask your students to do the same. This may feel clunky at first, but it really does make everyone feel involved in the conversation. Calling on people by name rather than pointing at them is another technique you can use to let everyone know who is about to ask a question or make a point. This has the added benefit of helping lecturers learn students’ names more quickly, and it is a great way to create a supportive community feel in the classroom.

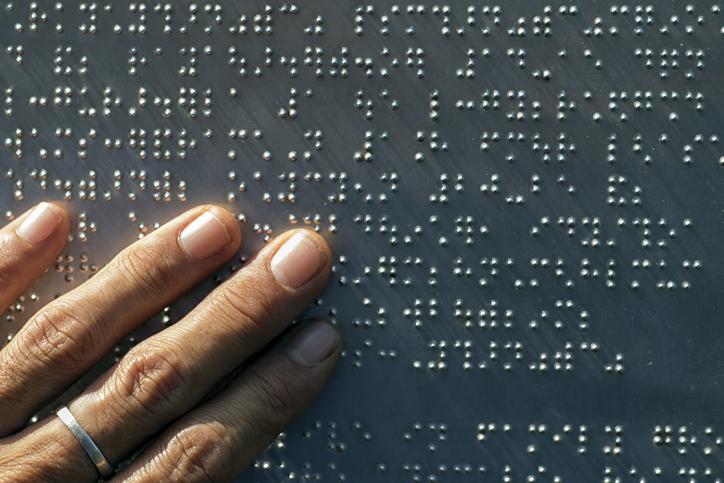

3. Make creative use of audio description

Audio description is the translation of visual material into words. If you are using images, graphs, tables or charts, it is important to put them into words as well as showing them on screen. Audio description is an example of what I call “blindness gain”; it is something developed by and for blind people that has unexpected benefits for non-blind people, too. Audio description functions as a kind of guided looking that makes images easier to understand and remember. People who lack visual confidence or who are non-visual learners (or who have simply left their glasses at home) will have an enhanced learning experience when information is delivered verbally as well as visually. Audio decryption is also a powerful pedagogical tool. Asking your students to describe an image or chart in words will always make it more memorable for them and more accessible for others. It also gives you a quick way of checking their understanding.

4. Make accessible documents the default

Use an accessibility checker such as Microsoft’s built-in tool to ensure that all your documents and slides are accessible. Once you are happy with your font, text size and document structure, create a template and use it for everything, whether there is a blind student in your audience or not. Many people who have hidden or undisclosed disabilities will benefit from accessible documents and the more we model accessibility good practice to our students, the more likely they are to create accessible documents themselves. Consider making accessibility part of the marking criteria for written and oral work. Penalising students who do not use dyslexia-friendly fonts or colour-blind-friendly contrasts sends a strong message about your commitment to access for all.

5. Share your accessible documents in advance

Showing an accessible PowerPoint on screen does not make it accessible. Students using screen readers need to access documents on their own machines rather than via Teams or Zoom. Always circulate your materials to all students in advance or upload them to Moodle or Blackboard before class for students to access if they wish. Not everyone is confident enough to request access adjustments, but everyone learns better when they can access a document in a way that works for them. Avoid sharing PDFs or scanned documents. They are not always accessible to screen readers. Instead, make accessible Word documents readily and easily available. Plug-ins such as Ally for Moodle will even convert documents to a student’s preferred format. I have lost count of the number of non-blind students who have told me they find listening to documents easier than reading them.

6. Don’t stop at teaching materials

Don’t pick and choose what you make accessible. Most universities concentrate on the student experience, but your colleagues and external partners will also appreciate inclusive approaches. Apply the above suggestions to meetings, open days, school visits, research events, café menus, graduation… There is little point claiming to be an EDI-confident institution if access begins and ends in the classroom.

Hannah Thompson is professor of French and critical disability studies at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her blog, Blind Spot, looks at blindness in history, literature, art, film and society. She was shortlisted for Outstanding Contribution to Equality, Diversity and Inclusion at the THE Awards 2021.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment