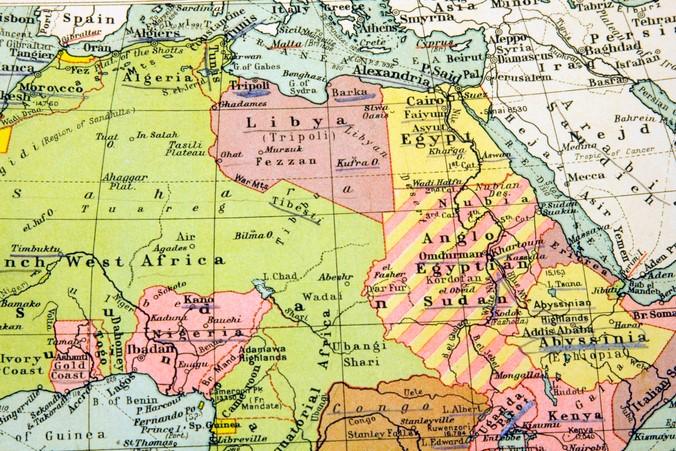

We set out to bring staff and students together to co-produce solutions to ongoing colonialism in our curriculum. One outcome is the “Mapping Decolonisation in Geography” project, an interdisciplinary student-staff collaboration looking at how to decolonise the teaching of geography. Here we share the principles that have made this innovative initiative a success.

1. Contextualising your decolonial efforts

Historically, decolonisation efforts at the University of Exeter have happened in isolation – unpaid, unrecognised and with minimal opportunities to share good practice or join forces across disciplines or even within individual programmes. Strategic initiatives such as the Transformative Education Framework – which uses “the power of education to transform our students’ lives so that they, in turn, can transform the world”, focusing on inclusive education, racial and social justice, and sustainability – have changed this, reinvigorating decolonisation efforts by offering recognition and, crucially, support. This has facilitated both discipline- and institution-level research about attitudes towards, and practices of, decolonisation, which have allowed academic and professional services staff to work as a collective and be more targeted in our approaches.

- Resource collection: Decolonising the curriculum

- How to support academic staff starting the journey of decolonising the curriculum

- Power and possibility: the role of universities in decolonisation

2. Defining ‘decolonising the curriculum’

As an institution, we conducted a series of lectures and workshops – open to all students and staff interested in attending – to discuss what “decolonising the curriculum” means, individually and as a community. This was not just about semantics; it was also a means of identifying our intended goals and the steps needed to achieve them. We published the agreed definition in our “Decolonisation Toolkit”, which is hosted on our intranet. Students and staff are encouraged to revisit it regularly and suggest updates as needed.

Indeed, defining decolonisation is something we do at the start of each decolonisation project, such as Mapping Decolonisation in Geography or bespoke projects initiated by politics and STEMM staff. We repeated this process when we collaborated with partners at Jadavpur University on an external “Introduction to Decolonisation” website, funded by the British Council.

This might seem redundant, but, as mentioned above, context is key, and it is crucial to ensure all shareholders have a shared vernacular and goal.

3. Narrowing your focus

“Decolonising the curriculum” is too broad a goal to be easily actionable, so it was important to narrow the focus by identifying aims that were more practical – and easier to evidence and evaluate.

Regular conversations were made possible because decolonisation was made a standing agenda item at education awaydays. Staff with more experience in the decolonial praxis embraced vulnerability, sharing their nascent decolonial teaching practices and encouraging both mimicry and critique.

To address decolonisation in geography, those teaching within the geography department collectively agreed it was vital to reconcile approaches across the divide between the discipline’s two main branches: the BA, or “human” geography, where staff were relatively aware of and open to decolonisation; and the BSc, or “physical” geography, where staff were supportive of decolonisation but unsure whether or how it might relate to their content or practices.

To inform this work, it was necessary to understand the views, knowledge and experiences of both staff and students in these two branches – hence the decision to map decolonisation across the entirety of the department’s curriculum.

4. Creating your team

To ensure the departmental project was both informed by and able to contribute to wider institutional goals – and to avoid siloing – geography staff partnered with a colleague in academic development who had previously led the development of the Decolonisation Toolkit. Student perspectives were provided by two paid interns who drew on their individual experiences – one each from the BA and BSc strands. We have continued to expand and diversify as the project has progressed.

5. Not making assumptions

Early in the project, we realised that staff and students might have very different experiences of decolonisation in the department. Specifically, we suspected that some decolonial techniques were going unnoticed – and perhaps students were even appreciating some approaches that were only inadvertently decolonial.

To explore this possibility, we developed bespoke survey and focus group questions for each target audience. Each question spoke to three overarching areas:

- What decolonial approaches are staff using?

- What decolonial approaches are students experiencing?

- What are our next steps?

We did ultimately find differences in student and staff perceptions, exposing gaps that needed to be closed and addressed in later stages of our project. This result emphasised the importance of carefully considering the assumptions and questions that underpin any project.

6. Generating achievable goals

Because decolonisation is a complex, time-intensive and iterative process, we understood the danger of defining a specific endpoint for our work. We always pitched the mapping project as being the first stage of many to follow. It culminated in the creation of five core goals to guide our future efforts:

- Normalise: Normalising decolonial approaches and methodologies, but also allowing space for being unsure because this is a learning process for us all.

- Make visible: Increasing staff and student awareness of decolonial initiatives to encourage open and honest communication.

- Encourage: Fostering curiosity and support for decolonising.

- Interact: Using everyday spaces such as seminars, lectures and meetings to discuss decolonisation and encourage collaboration.

- Structure: Diversifying the staff and student body in an inclusive way and rebuilding structures that bias the white, male, heteronormative, upper class and Anglocentric opinion.

Although these goals were specific to Mapping Decolonisation in Geography, we aimed to keep them useful for other departments (and institutions) wanting to follow our process.

7. Keeping momentum

We believe that decolonisation cannot be achieved. Instead, we must persevere in ongoing decolonising. This sentiment was captured eloquently by a third-year BA student who responded to our survey saying that we are on a “continuous learning journey”.

To this end, we will continue to experiment with novel approaches, exchange ideas with new collaborators and supporters, value our student expertise – and, of course, take a reflective approach in what we do. We shall continually map our decolonial progress to navigate towards a more equitable learning community.

Caitlin Kight is a lecturer in education studies and Eleanor Cook is transformative education assistant, both at the University of Exeter.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment1

(No subject)