The pedagogical approach to learning, teacher-centred learning, the sage on the stage – call it what you will, things aren’t looking good for this particular learning model going forward.

The future looks very likely indeed to include a pandemic-induced move toward a new hybrid era that mixes online and in-person study. Furthermore, the spoon-fed style of learning is not best suited to prospective PhD candidates, future researchers or adult learners looking to develop their career through study.

With this in mind, universities would be wise to embrace more andragogical (learner-centred) teaching practices in order to maximise educational efficacy in a world where students are less likely to be physically present in a classroom or lecture theatre.

This is especially salient for those who wish to pursue level 8 education, namely a PhD, which is entirely self-directed in nature.

First, though, we should perhaps cover in a little more depth what andragogical learning actually is.

Andragogical learning is the opposite to pedagogical learning, in that pedagogy is a teacher-led approach defined by the primary school classroom, for example (“peda” being derived from the Greek for child and “agogue” meaning leader). It is a model of learning that, for many, largely continues until they finish their undergraduate education. Andragogy is different in that the process of learning is directed by students themselves (“andr” being derived from the Greek for man).

Cornerstones of the andragogical approach to learning include a focus on process rather than content. Ultimately, students aren’t being aided with ready information, instead they are exploring, researching, discussing and collaborating to find out the best response or approach to a real-life scenario. Tutors act more as facilitators, helping students to analyse and resolve the issues presented to them.

Linked to this is the requirement for higher-order thinking practices as demonstrated by independent thought, critical analysis and appraisal and reflective practice.

Combine this with experiential learning techniques, such as role play simulations and group learning, and you have the foundation of an andragogical learning environment that yields impressive results as adults learn at their optimum level. This lays the groundwork for continued academic development, where PhD students are required to become truly independent researchers and learners.

And of course, let’s not forget that beyond academia many of these practices are equally well applied to the corporate world of work where graduates are expected to demonstrate work-ready skills, including problem solving, active listening, teamwork and decision making, beyond those of the specific skills required for the job itself.

Indeed, you will often hear many employers lament the lack of these work-ready skills in new graduates, who have been largely spoon-fed for their entire learning journey then struggle to transition into the role of autonomous employee, leaving their student persona behind.

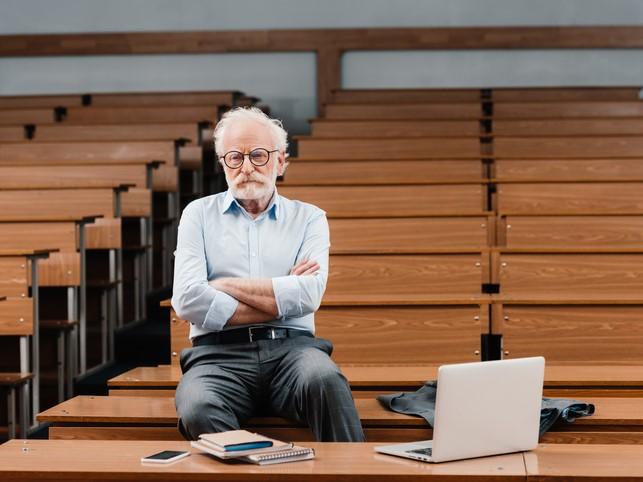

So why is it, then, that many universities continue to heavily rely on pedagogical teaching practices when it is proven to be the less effective way to learn as an adult?

The reality is that many university courses have been developed with the requirement to be able to teach up to several hundred students at the same time, as opposed to smaller groups facilitated by tutors.

Clearly, the economics of learning is very much at play here. Universities understand that andragogy and not pedagogy is what the average adult learner requires, but andragogy can be difficult to apply to the masses when it comes to in-person learning.

The online education space fares much better in this regard, with most well-regarded online learning providers building their models around purely andragogical methods and utilising the latest educational technology to help encourage and monitor engagement and interactivity.

It also helps that an andragogical approach works well for part-time learners, who may be combining learning alongside a job and need to maximise efficiency in their learning journey. Furthermore, such learning allows students juggling a career with gaining new qualifications to take the knowledge, research and simulated scenarios undertaken on their course and directly apply them to their real-world work, be it medicine, finance or marketing, immediately benefiting both them and their employers. A win-win.

It’s also worth pointing out that for mature students who have returned to education after many years, or even decades, and all the experiences this brings, a pedagogical approach would likely do them no favours as they adapt to being a student once more.

While pedagogical techniques do of course have their place – like many of us I have been inspired and fascinated in equal measure by many a charismatic lecturer over the years – it’s important to recognise that andragogy is the key to harnessing the brain’s potential.

After all, would you rather hire someone who was adept in critical thinking, problem-solving, communication and initiative? Or would you rather someone on your team who was talented in the art of lecture notes? While I appreciate a thorough set of notes as much as the next person, as an employer I know which one I would prefer.

Steve Davies is professor of medical education at the University of South Wales, a consultant physician in Cardiff and the founding director of Learna, a provider of postgraduate online education.

comment1

(No subject)