Inclusion is a matter widely discussed in higher education. However, it is often treated superficially in ways that do not translate into educational reform, our past research suggests, reducing it to academic “chatter”.

We recently conducted a new piece of research to analyse inclusion policies of elite Russell Group universities and found that inclusion was becoming something of a new quality and performance indicator, potentially enhancing a university’s global reputation and ability to attract students and staff. There should be recognition, though, that inclusion is linked to the core purposes of higher education – or that it can, at least, challenge narrow perceptions of these purposes.

We had further opportunity to reflect on these issues through involvement with the Erasmus+ SPISEY (Supporting Practices for Inclusive Schooling & Education for Youth) project, with partners from Denmark, Finland, France, Spain and the UK.

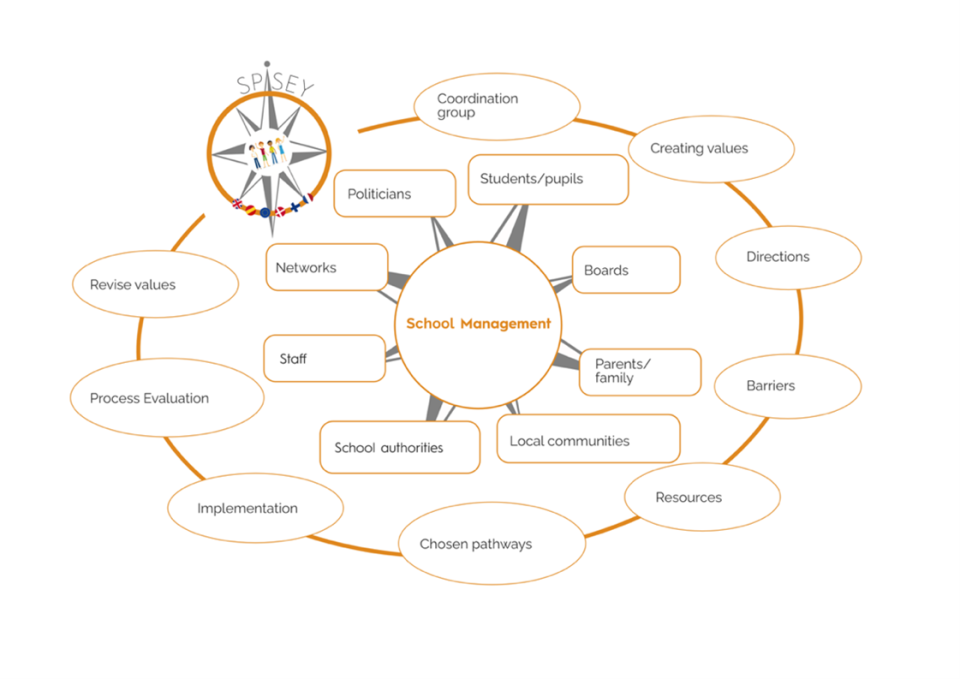

SPISEY set out to examine ways of fostering social inclusion in participating schools in the five countries, building on the Inclusion Compass, a management tool originally designed in Denmark. However, Covid-19 forced each partner to seek alternative plans. With very limited access to schools during 2020-21, the UK team decided to conduct the study within our institution, translating the aims and focus of the project to inclusion in higher education.

We conducted a survey, workshops, one-to-one interviews and focus groups with students, academics and professional staff to discuss ideas about inclusion and how the Inclusion Compass could be used to guide thinking and planning about inclusion.

The way students and staff described inclusion was particularly striking. One of the students said that a more inclusive university community would be one where “people would have to know who I am”.

Lack of inclusion was discussed as a form of absence, with people and groups seen as being literally and metaphorically “shut out” of spaces and activities.

Participants indicated that the Inclusion Compass could be a useful tool in terms of institutional inclusion planning as it might:

Help identify gaps in provision

The Inclusion Compass involves detailed mapping of relevant stakeholders, and this can be an opportunity for a university leadership team or inclusion working group to ensure there is provision available for all groups within a university community.

Thus, the tool can help identify gaps in provision for particular groups of students and, most importantly, groups who can be less vocal, eg, international students, mature students and students from minority groups, such as students with disabilities or LGBTQ+ students. Given the pressures of the pandemic, this also applies to members of staff who often experience considerable workload and well-being challenges.

Give voice to stakeholders, and especially students

The Inclusion Compass could, for example, be used as a tool to guide discussions and planning within equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) student groups or focus groups to show that their voice is important and valued within the institution. Using a particular tool to guide decisions about inclusion can help ensure that different voices and perspectives are not lost. This connects to the next point – that discussions about inclusion need direction and structure.

Help provide direction and structure in discussions about inclusion

Since inclusion is a complex matter affecting every organisational level and group within a university, inclusion planning ought to be based on a particular framework that can provide structure and guidance. This framework would need to be flexible enough to accommodate different institutional communities with unique characteristics (more or less diverse, large or small, more or less open to change). The Inclusion Compass can be used to provide this structure, while emphasising that inclusion is not just a top-down vision but the product of ongoing whole-community negotiation.

Promote stakeholder engagement, especially for minority and hard-to-reach groups

In discussions we had around the use of the Inclusion Compass, we discussed the experiences of mature students and students who have caring responsibilities who can be “left out” of discussions. The compass can ensure that inclusion values are negotiated across all university communities rather than expressing the interests of particular groups.

At a dissemination event as part of the project, we discussed how to ensure that tools like the Inclusion Compass are used by universities, and the following considerations emerged:

- How would the Inclusion Compass fit with your practice?

- What would engagement with the Inclusion Compass look like? Would you be doing this individually, within programmes, within disciplines? And how often?

- Which members of the university community would be best suited to lead on conversations using the Inclusion Compass (for example, student leaders)?

- What would be the best way to get various tools into people’s hands? Webinars, face-to-face events, dedicated website, emails, newsletters?

- What kind of support would you need in applying and interpreting the tools? What kind of team would be most relevant to offer support?

There are no single or easy responses to these matters, and they would have to be negotiated within particular university communities. However, one of the main potential barriers highlighted was the lack of time for staff and students to engage deeply with matters of inclusion and make more radical changes. This suggests that making time is critical to achieving intended goals around inclusion.

The SPISEY project gave us the unexpected opportunity to debate matters of inclusion within higher education, as well as with partners in Europe. We hope projects like SPISEY can help to spark further discussion and reinforce that inclusion lies at the very heart of higher education – it is not just an empty word used to satisfy legal requirements or achieve promotional purposes. This, in turn, will help ensure higher education communities promote visibility, recognition and belonging, so that we really know who everybody is.

George Koutsouris and Lauren Stentiford are both senior lecturers in education, and Tricia Nash is a research fellow, all in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Exeter.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment