What do W B Yeats, Bertrand Russell and Charles Bukowski have in common? Apart from the fact that all three were influential figures in their time and were what we would call “important thinkers”, they also had a similar view on one of the reasons our time is somehow troubled.

Yeats, in his 1920 poem The Second Coming, concluded that “the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity”. Russell, 13 years later, in his essay The Triumph of Stupidity, wrote: “The fundamental cause of the trouble in the modern world today is that the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”

When these two men wrote the above, there was no internet, no information overload and the “podium”, so to speak, was reserved for those with the status or (in my favourite version) the knowledge necessary to make their opinion heard. Bukowski’s similar views on the issue, half a century later, coincided with the dawn of the digital era – or what we today call “the information age”.

- Students aren’t giving up social media, so teach them how to question it

- We’ve forgotten how to communicate science to the public at a crucial time

- Address bias in teaching, learning and assessment in five steps

In our “consume and move on” culture, we find ourselves inundated with information, “experts” and ideas that sometimes lack grounding, are built on uncertain credentials and, perhaps unsurprisingly, often expire more quickly than last week’s groceries. So, what can we do to counterbalance misinformation and disinformation and debunk popular myths within our own disciplines?

Sadly, there is no single failsafe way to achieve this, but some useful techniques can help.

Get your audience asking themselves questions

I’ve found it effective to engage with my audience through a journey of questions and uncertainties to a conclusion of self-realisation.

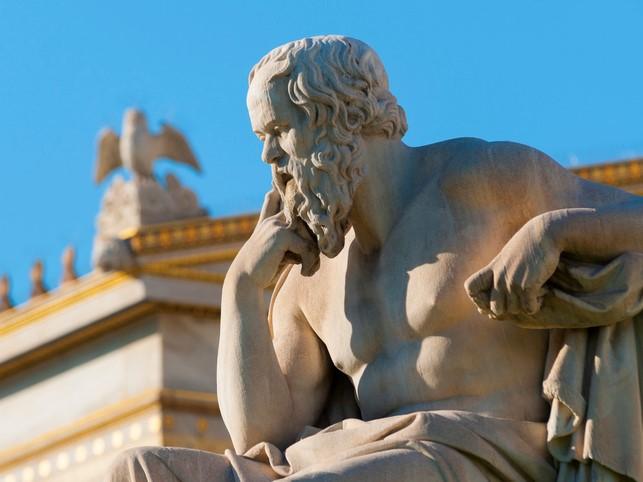

Perhaps influenced by my DNA, I turn my gaze to Ancient Greece. Socrates developed his maieutic method (also known as the Socratic method) to combat exactly the same problem more than 2,000 years ago. He would engage his students, or fellow diners, in conversations where he would set questions designed to provoke controversy and uncertainty. In Ancient Greece, lots of philosophical discussions took place during symposia, where food and wine were plentiful.

In modern academics, too, it can be a helpful tool to use exaggeration to plant the seeds of enquiry in everyday practice.

For example, I had a couple of my actor friends dress as policemen, barge into the lecture theatre while I was discussing the issue of obedience with a group of students, and “arrest” me for a crime committed precisely a week before. What would my students do? They knew I could not have been responsible. I was with them at the time, miles away from the crime scene, discussing a different topic. Would they confront authority or simply obey? Making students think on their feet and allowing questions to directly relate to something they’d seen meant that the discussion that ensued after my (minor) deception was exposed was as vibrant as it was interesting.

Say less

Socrates’ aim, above all else, was to spark a debate and then say as little as he possibly could, watching his collocutors come to the realisation that their initial position was based on unsupported assumptions and misconceptions. As the Unabridged Dictionary puts it, the goal was to “elicit a clear and consistent expression of something supposed to be implicitly known by all rational beings”. In other words, Socrates’ idea was to encourage someone to elaborate on a position he believed to be unscientific and false, so they would ultimately reach a point where they realised the fallacy of their initial premise and emerge with a new understanding of the topic discussed.

Such an approach can be encouraged by providing your student audience with the opportunity to share their views with their colleagues and yourself more regularly. Something I have done successfully in my classes is establish a weekly “an audience with…” format, in which students present and support their positions on a preselected topic. They have 15 minutes to communicate their views, followed by 15 minutes where they take questions, and it has proved greatly successful in encouraging students to question their own and others’ ideas.

Embrace modern approaches to communicating ideas

Socrates’ approach, as noble and effective as it might have been in his time, would likely suffer greatly nowadays largely thanks to a thoroughly modern ailment: whenever we are trying to convince someone, they need to be willing to be convinced.

As difficult as that might be in our supremely partisan world, all is not lost. Joseph Joubert, an 18th-century novelist, wrote that “the aim of argument, or of discussion, should not be victory but progress”. The truth of such an idea, perhaps now more than ever, should be our modus operandi, and we need to promote our expertise with a new set of tools in addition to the traditional use of facts and reason.

With the aforementioned podium now available to anyone with a camera, smartphone or personal computer, expertise (and the truth it professes) should not simply be advertised as just that but as the “natural” conclusion in any given discussion. Asking questions and encouraging our collocutors to challenge our and their own systems of thought might prove to be a powerful ally as we strive to fight misinformation.

Going above and beyond to demonstrate to our audience that our difference in position over an issue does not stem from emotion or sense of entitlement but rather results from our investment in time and effort becoming proficient in our field can be the key to unlocking our counterparts’ defences and earning us their attention. The rest is up to us.

Konstantinos Arfanis is a lecturer of psychology at Arden University, UK.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment