What is the ‘slow movement’?

The slow movement “may be variously embodied by subjects or practices depending on the context in which ‘slow’ is being configured against forms of ‘fast life’”, according to Wendy Parkins and Geoffrey Craig. Even a quick dip into Carl Honoré’s best-seller In Praise of Slow reveals that proponents of the slow movement are not insisting that slow is always best. Rather, they are calling for balance within our increasingly technologised, streamlined and efficiency-maximised experience – a deliberate and mindful inclusion of slow moments within our busy lives. To quote Honoré, slow living “does not imply that all actions must be taken at a tortoise’s pace. Rather it means resisting the pressure to do everything quickly, and instead consciously choosing when to be slow and when to be fast. It is…about finding the tempo giusto, or the right speed”.

- THE Campus spotlight: how to reconnect in a changed world

- Virtual classroom connections: enhancing three presence elements via online tools

- Pedagogical wellness specialist: the role that connects teaching and well-being

Why is this important in the classroom?

In our pacy and technologised world, isolation and alienation are ever more prevalent and problematic. Many aspects of learning are inherently social, and often – especially in on-campus learning – we rely on the sociable nature of students to take care of this important element of learning. However, our recent online classroom experiences have highlighted how much we, as teachers, take this for granted. In the online classroom, deliberate and scaffolded opportunities and spaces are required to facilitate these important interactions. What can we take away from these online experiences to enhance the on-campus social classroom experience and perhaps create more inclusive social learning experiences for all students?

What are the key elements that can be drawn together from online learning and the slow movement?

The key thing we have learned from reconceptualising the classroom and social, collaborative learning for the online space is the need for deliberate action and time. And these two elements are readily transposable back on to campus.

We all have handbooks full of codes of conduct, classroom values, guidelines for team working and even policies on bullying and harassment. But do we ever go further than stating what behaviour and practice we want to see, and, even more likely, what we deem unacceptable? Do we create space to facilitate good interactions, provide feedback and support on furthering those connections and even model those behaviours ourselves?

In building effective connections in the classroom, our approach as educators must be:

- Deliberate

- Explicit

- Purposeful

- Foundational

Building connection in class

We must place value (and time) on these moments – including being up front about the nature of the activity. Here is an example that we used repeatedly in our online class to help students begin to connect with others and normalise their own experiences. We set the following prompt:

“When you join the class Zoom at 4pm, please do straight to your team room on Zoom to catch up with your team. Catch up and share one thing that has gone well for you this week (in this module, your studies or life in general) and one thing that you have struggled with.”

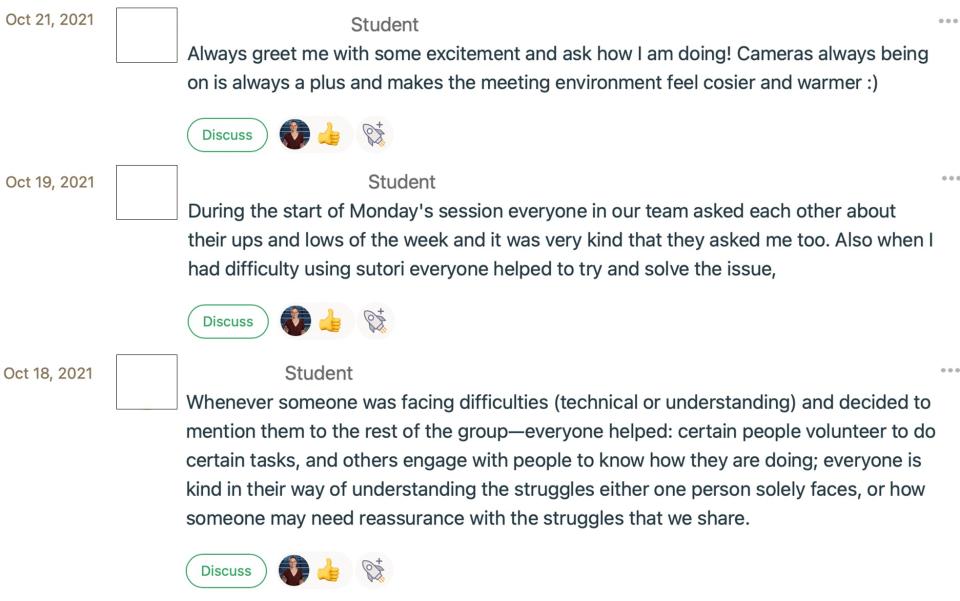

At the end of the class, we asked students to reflect on what they had learned from other students during the class – this did not have to be related to this initial activity, but most students commented on this early discussion activity. The students reported feeling better about themselves after hearing how their peers also struggled with deadlines, life and confidence.

However, to make these connections meaningful and long lasting, there needs to be something more than just a series of good but isolated connections. There needs to be a culture of connecting. And for this, the educator needs to ensure that the activity is:

- Structural – built into the fabric of the class

- Modelled – embodied and enacted by the teacher

- Acknowledged and positively reinforced by the teacher

- Linked to learning

In an activity that aimed to set a tone for our classes and establish a more connected culture, students were told at the beginning that by the end of the class, they would be asked to report something kind that another student had done for them during that session. This required students to think beyond their own activity and take an active role in creating a culture of kindness. What could the individual student do to prompt another student to offer kindness to them? This might be modelling kindness themselves, it might be sharing a vulnerability to allow another student to show kindness – this was left completely open for the students to puzzle over.

By the end of the session, we had a message board overflowing with kind acts. As the teacher, I had been nervous about appearing over-emotional, embarrassing myself and the students by using the word “kindness”, but in fact the students were hungry for this activity and embraced it both in this session, and without further prompts in future sessions.

Normalising emotional responses in class

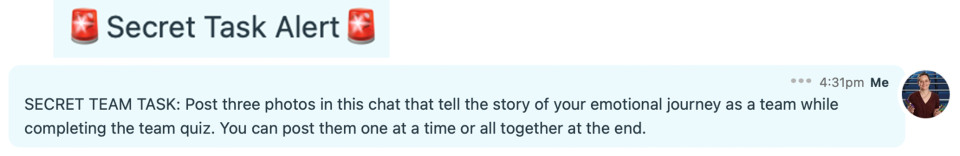

A further stream of activity aimed to normalise a range of emotions within the classroom – and specifically within class activities and learning. We created a special chat stream for “Secret Tasks” during the live classes. These tasks asked students to reflect on their learning as they were enacting it – identifying different aspects of the learning experience. In this way, we began to establish links between the emotional, social and interactional elements of our classroom and individual learning and success.

Educators should try to normalise the experience of anxiety, disappointment and exhilaration in the service of learning – finding ways to share and understand these very natural responses.

In a low-stakes, multiple-choice quiz, students were asked to collaborate to answer 10 questions. They receive their score, but no feedback. They have two opportunities to resubmit their quiz responses – but without knowing which questions they have got wrong or right. This is a golden activity that highlights the importance of feedback and works on negotiation and critical thinking skills. By asking students to post images of their reactions to each score, it allows a safe examination of our emotional responses to uncertainty, (minor) failure and success.

Building good academic practice

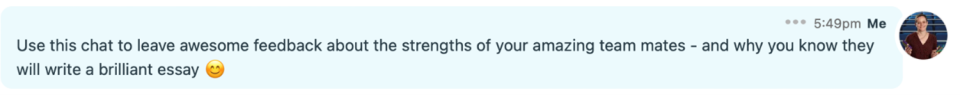

More moments of connection, of showing ourselves and seeing others, allow us to establish good working practices – such as seeking feedback. Here is an example of a task I regularly set students to encourage them to actively seek feedback on their work:

“Capture as much photographic evidence as possible of your team accessing feedback from Dr Hauke before the end of today’s session. Post your evidence in this chat by 6pm. Serious kudos to the team with the most evidence [evidence might include selfies, screenshots or other more creative ideas].”

Finding confidence and courage from others

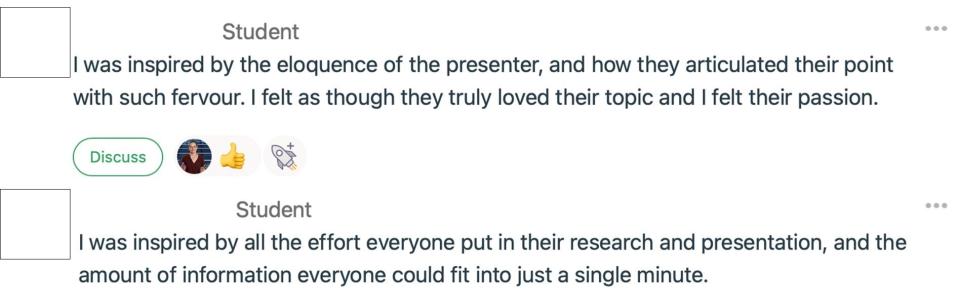

Lastly, as well as helping students build meaningful connections and establishing a classroom culture of kindness and collaboration, these types of activities support the development of networks of peer support and celebration.

When approaching a final assignment, with a classroom full of uncertainty and nerves, the students can displace that anxiety with confidence and encouragement – sharing what they know to be true about each other. It can be difficult to find our own confidence, but easier to see and say what other people are capable of achieving. Ask students to share those insights in order to build their sense of positivity and see the views others hold about them in order to reconsider their own doubts and fears. If other people believe in us, perhaps we can believe in ourselves.

And, of course, it is important to celebrate and value each other. Ask students to share what they admired or enjoyed about one another’s work. Here students are noting what they enjoyed about an afternoon of student presentations:

Key takeaways

- The slow movement is about establishing meaningful connections and engagements rather than about acting “slowly”

- Building meaningful connections and engagements takes time

- A deliberate, explicit, purposeful and foundational approach helps signal the value that we as educators place on these moments, allowing students to see their value

- Building these elements into the structure of the class, modelling and embodying these connections and values, acknowledging and positively reinforcing these moments and linking them to learning are key to establishing a unifying culture of connectedness beyond the individual moments

And this is a final comment from a student, left spontaneously in their module feedback:

“It was all the time we spent together. I mean, we did an awful lot of things, I don’t think I’ve ever done so many things, but we also just spent time together. We had time to do everything, and we worked very hard. But we also had time. It’s like, being at [university] is like being on a train. You’re rushing along, and you can’t really see everything passing by out the window because you’re moving so fast. And coming to this class was like stepping off the train for a couple of hours. Just standing on the platform, watching the train rush on past, and just being still.”

Elizabeth Hauke is principal teaching fellow, Change Makers, Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication, Imperial College London.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment1

(No subject)