Over the course of the pandemic, educators – like everyone else – were forced to rethink the way in which we do our job.

And, like most people, we responded by seeing how we could do basically the same thing in a slightly different way. Classrooms gave way to Zoom rooms; in-person exams gave way to remote tests, with varying degrees of surveillance to guard against cheating.

For the most part, however, it was business as usual: one teacher, many students; a flow of information followed by a smattering of questions; tests administered uniformly and graded on a curve.

But the pandemic’s push to experiment with online materials has also brought to the fore the possibility of replacing traditional educational models with ones enhanced by technology.

On the supply side, rather than watching a video of your professor give an introductory lecture on a topic, there are now world-class faculty offering such videos for free. No university expects to produce all of its own textbooks – might we one day think the same of lectures?

On the demand side, computerised adaptive learning and testing offers more personalised educational models. All teachers know the difficulty of pitching a class to students with mixed abilities. Interactive online modules enable students to repeat topics with which they have difficulty – or skip ahead if they’re bored.

- Expert Q&A: Active learning – engage learners across modalities

- Top five strategies for integrating active learning into virtual classes

- Video: How to design an online course centred around interactive learning

None of this is new to those who have been experimenting in this area for years. “Flipped classrooms” and blended learning predate the pandemic. Yet the broader conversation is helping clarify the problem that we’re trying to solve.

One of my own reservations about many flipped classroom models is that they use videos to replace lectures. It’s great that class time is then spent on project work or interactive discussion, but both the lectures and the videos are trying to make up for the fact that too many students aren’t preparing for class by doing something much more basic: reading.

If we aren’t confident that students will read before coming to class, why do we think they will watch videos? And even if they do watch those videos, many will do so while multi-tasking – or at increased speed. This is efficient in terms of time, but not always conducive to rich understanding.

More fundamentally, the tendency is to conceive of these new educational models as a mix of synchronous and asynchronous activities – ten-dollar words that mean doing some things at the same time and others on your own time.

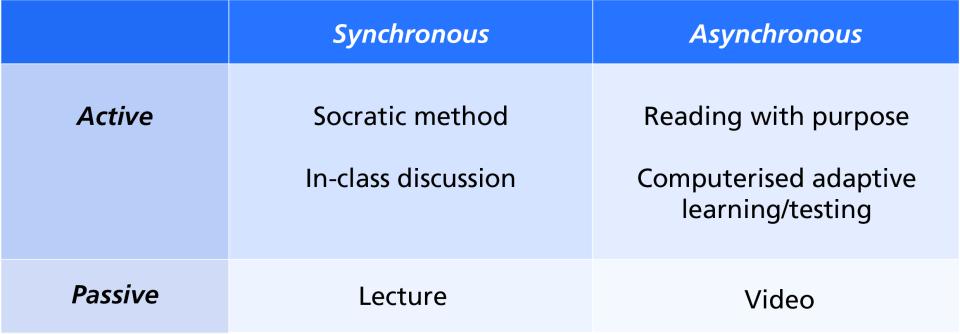

A more important distinction, I would argue, is between active and passive – leaning into something or sitting back and letting it wash over you. This may be either synchronous or asynchronous. Combining the two sets of categories gives us a two-by-two matrix that maps out discrete learning options and some of the possible modalities.

Videos and large-format lectures would both be in the “passive” row. Active alternatives would include discussion-based classes and paper- or computer-based work that requires student engagement.

Viewed this way, the shift from lecture to video solves the pandemic problem but not the pedagogical one.

The true challenge for academics is not to shuffle between synchronous and asynchronous, but to move from passive to active. The benefits are obvious in terms of educational outcomes.

But so are the costs.

Smaller class sizes have long been the privilege of elite and expensive universities. It’s possible that technology will make personalised learning modules more widely available, and for many universities this will raise invidious choices about outsourcing some of their activities – with the risk that it will dilute brand or stop students enrolling in the first place.

If all your computer science classes are “taught” by watching videos from MIT or Google, for example, will students still pay for your “degree”?

It’s easy to imagine tertiary education going the way of consumer goods, with dominant actors such as Amazon and Alibaba delivering exactly what you want (sometimes before you even know you want it) and squeezing out the competition.

And yet I remain optimistic about universities. Because a big part of the experience of a university is not the interaction with the professor in the classroom (real or virtual), but interaction with fellow students in the hallways and around campus.

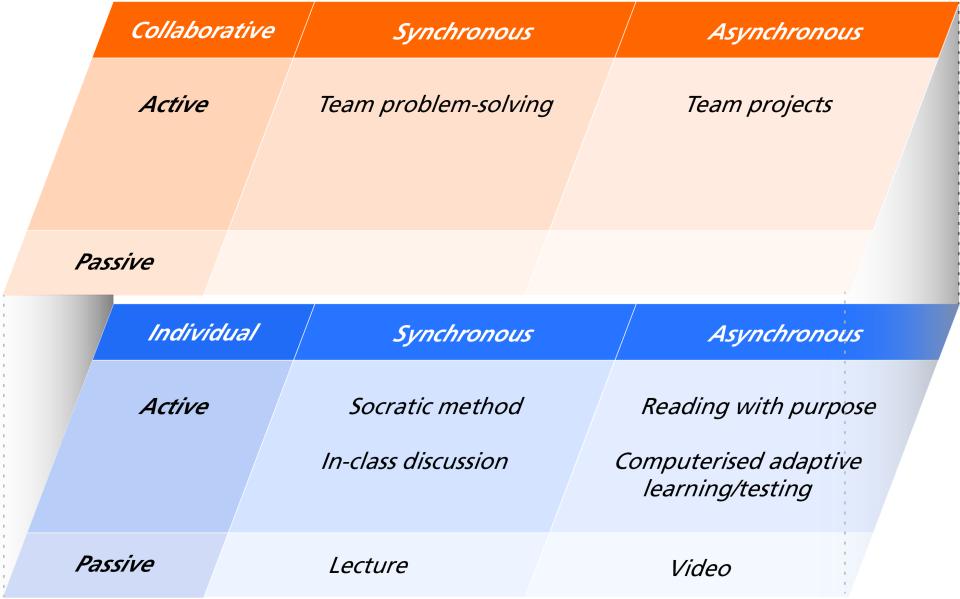

Indeed, the two-by-two matrix above misses out this aspect of education, which we might loosely term individual versus collaborative. Adding that dimension would incorporate the team-based problem-solving often used in flipped classrooms, or group projects pursued out of class hours:

Technology will continue to increase the options available to educators and – eventually – pandemic restrictions will cease to limit them.

Some universities have already repurposed their lecture theatres; a few have even been built without them. As the rest of us move back into our classrooms, the temptation to go back to business as usual will be strong.

It should be resisted.

In its place, we have an opportunity to rethink education drawing on the best mix of active and passive activities, some synchronous and others asynchronous, with a mix of individual and collaborative learning activities tailored to the educational needs of our students.

Simon Chesterman is vice-provost-designate (educational innovation) at the National University of Singapore, and dean-designate of the new NUS College. He continues to serve as dean of the Faculty of Law.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment1

(No subject)