Bad academic practices are actions that don’t line up with an institution’s stated standards and guidelines for academic work, although they may assume different forms depending on who engages in them. Sometimes students carry out unethical academic conduct unintentionally through lack of awareness of what constitutes bad practice or a lack of knowledge of how to conform to it.

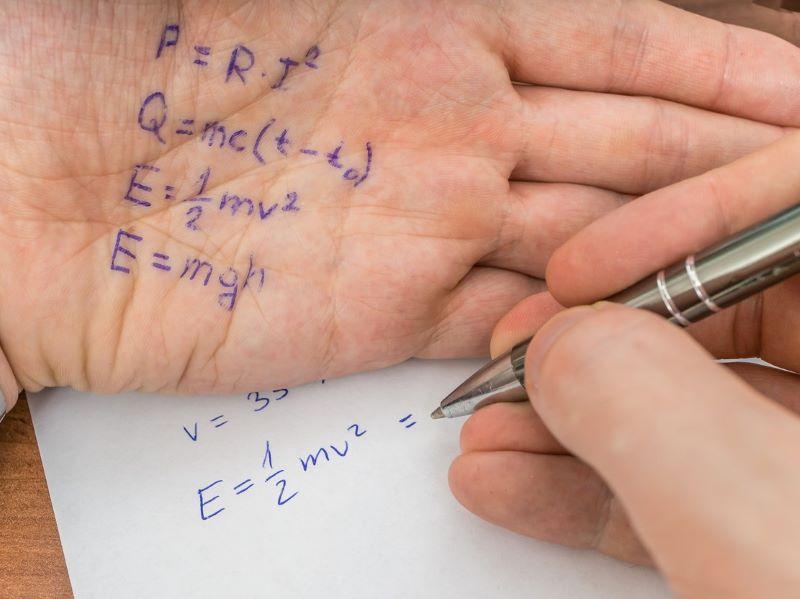

However, many students’ participation in unethical academic conduct is intentional. Examples include plagiarism, fabricating laboratory/survey data, impersonating another student during an exam, cheating by copying, or falsifying official documents such as letters of permission or recommendation. So, how should an educator discourage unethical behaviour and promote academic integrity and honesty among students?

To address the issue of academic misconduct at its root, educators must be proactive, prioritising developing students’ awareness of acceptable academic practices. Concentrating on changing students’ mindsets before the fact helps address the problem at its root rather than waiting for an offence and then handing out a punishment. If students are not sufficiently informed on why some academic practices are unacceptable, they may be more likely to engage in them. It’s not uncommon to learn, following an incident of unethical conduct, that a student didn’t know they had done anything wrong.

- Promoting academic integrity in a massive online master’s programme

- How to design low-stakes authentic assessment that promotes academic integrity

- Zero cheating is a pipe dream, but we still need to push academic integrity

A brief orientation can be scheduled within a lesson to raise students’ awareness of academic misconduct. However, informing students of the benefits of abstaining from such behaviours shouldn’t stop after one or even a few classes; it should continue throughout their time at university. After all, repetition is key to persuasion.

Furthermore, such an awareness campaign should go beyond words. Students will not take integrity seriously if their teachers do not uphold it as a key priority. To create a culture of honesty among students, teachers must be examples of morality and ethics themselves.

Besides awareness, additional steps need to be taken, especially among students who engage in unethical behaviour intentionally. Criminal behaviour is often motivated by a belief that the projected benefits outweigh the costs, and when this is deemed the case by students the likelihood of academic misconduct rises. As such, the more steps taken to expose cheating, penalise it severely and reward honesty, the fewer students are likely to participate in unethical behaviour.

Students’ participation in such conduct often decreases when they are aware of the repercussions. Before an exam, for example, even a simple verbal warning, along with information on the consequences, can discourage cheating. Teachers must specify strong sanctions in line with their institutional standards. Academic misconduct will usually decline if students who engage in unethical activities realise that the costs exceed the perceived advantages.

Since bad habits can easily develop into a deeper attitude, it stands to reason that students who are involved in fraudulent practices in university might engage in other unethical behaviour in the workplace. As such, teachers who are slack in dealing with academic dishonesty run the risk of producing unethical future professionals. This could have profound effects later since these students will often be the future leaders of society, holding positions that will shape policy and more. Therefore, in many ways, educators are the first defence against the spread of unethical behaviour, helping guarantee quality delivery and a better society.

Students who engage in academic misconduct demonstrate a lack of understanding of what education entails. Of course, the stakes are high: many students cheat to achieve good scores that will increase their prospects of receiving scholarships, acceptance into graduate programmes and future employment. But they must understand that while aiming for a good grade is a positive thing, how that grade is obtained must also be good.

If students are aware of the grievous consequences of using unethical means in their academic pursuits, both for their own lives and for society, they will probably be more willing to abstain from engaging in academic misconduct.

Victor Markus is assistant professor of medical biochemistry in the faculty of medicine at Near East University, Nicosia, North Cyprus.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment