Students belonging to groups that are under-represented in higher education – for example, young members of certain ethnic groups, disadvantaged or first-in-family university students – face unique obstacles in adjusting to the academic community. Due to socialisation that differs from the majority and typically lower educational preparedness, they are frequently not familiar with the norms of the academic environment.

These students often report feeling stuck between two cultures or groups. As under-represented minority students try to adjust to their new academic environments, their ties with their communities of origin are weakened since they cannot easily share their academic experience or challenges. And while their community ties are weakening, their ties to the academic community are not strong enough to allow for successful adjustment.

- For diverse communities to thrive, we need intersectional policies and practices

- How to tell if your university is making a genuine effort to increase diversity

- HE has a crucial role to play in reaching out to indigenous communities

Balancing between the origin (that is, a low-status family) and the host (the academic world) environments creates tensions and leads to different coping and adjustment strategies. However, what successful adjustment to college means is a matter of debate in studies investigating under-represented minority students: to what extent is it necessary to assume the identity of the majority society? And is separation from their community of origin a requirement or an inevitable consequence?

Ties matter

Students’ social relations and the resources available through them play a decisive role in adjustment to college. Both the kinds of ties students can rely on and the extent to which they can embed into the academic community strongly determine whether an individual will drop out and the successful completion of semesters and years spent in higher education, as well as their psychological well-being.

The case of Roma students

The case of Roma university students is special for many reasons. The Roma population is not only the most populous but also the most disadvantaged minority group in central and eastern Europe. The situation of Roma university students is intersected by their ethnicity, by their generally low social status and by the discrimination they face from the majority society. We intended to get a deeper understanding of Roma students’ adjustment to college from a social aspect by capturing students’ real ties.

Our research involved 124 Roma university students from the Roma Colleges for Advanced Studies Network (RCASN), which aims to support Roma university students in obtaining degrees. Colleges for advanced studies are dedicated to supporting talented university students in their studies and academic work. These colleges provide special courses and offer accommodation in dormitories; students can also be awarded scholarships.

Exploring students’ personal networks

We aimed to understand what types of egocentric networks can be identified among Roma students, and what kinds of resources these provide. By analysing Roma university students’ egocentric networks, first, we explored the main groups in students’ personal networks:

- Origin group: Roma persons with lower than secondary education attainment

- Fellow group: Roma persons with secondary or higher education

- Host group: non-Roma persons with secondary or higher education

- Other group: non-Roma persons with lower than secondary education.

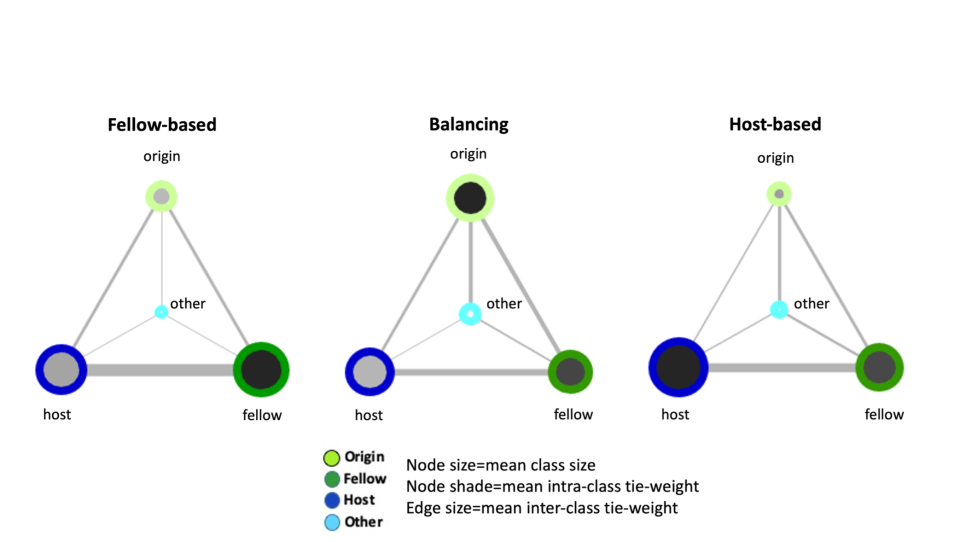

We identified the three most characteristic network types among Roma university students by cluster analysis based on the proportion of origin, fellow and host groups in students’ personal networks (see Figure 1).

Personal network strategies

Of the three clusters, the host-based cluster (48 per cent) is the most extensive and provides the most structural resources for students. Previous research showed that, for upward social mobility, the multicultural, extended network is the most ideal for under-represented minority students. Students with host-dominated networks who are able to preserve their origin ties possess both the emotional stability and the structural resources required to adjust to the academic environment.

The fellow-based cluster (35 per cent) illustrates well how small communities can have a key role in students’ adjustment to college. This cluster is a small network that is determined by the RCASN community. Small academic communities similar to RCASN colleges are able to stabilise the egocentric networks of students finding themselves in a social vacuum. However, it is important to note that while these communities provide stability in the network of under-represented minority students, they also limit the enrichment of university ties.

Networks in the balancing cluster (17 per cent) are the most well distributed regarding the proportion of the origin, fellow and host groups, although this network type also demonstrates how challenging it is to integrate these groups into one network. Research has shown that simultaneous connection to groups facilitates the formation of the complex identity of an individual, which suggests higher self-esteem and the ability to experience multiple layers of identity. However, conforming to the norms of different groups can be mentally demanding. While cluster membership does not show significant differences on the variables of self-esteem, life satisfaction, subjective state of health and trust, our results suggest that the students in the balancing cluster have poorer subjective well-being and trust than students in the other two clusters.

A foot in two worlds

Our study identified three main network strategies for under-represented students’ adjustment to college. All demonstrate that higher-educated Roma have a foot in two worlds: the community of origin and the academic environment. This constant balancing is the cost of mobility from the social network perspective.

As universities, we must emphasise the role of small fellow communities – such as RCASN communities – that can provide stability for students falling into a social vacuum by interconnecting the origin and the host environment. Communities with students of similar origins and with similar backgrounds create opportunities for students to experience their ethnic identities and, at the same time, provide them with the opportunity to engage with the university as a community with its own subculture, rather than internalising the norms and values of the majority.

Ágnes Lukács J. is a sociologist and assistant lecturer of the department of social sciences in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Semmelweis University, Hungary. She is an associate editor at the European Journal of Mental Health.

Beáta Dávid is the director and coordinator of the sociology doctoral programme of the Institute of Mental Health Sciences and deputy dean of scientific and educational affairs in the Faculty of Health and Public Administration at Semmelweis University. She is also head of the research department of the Center for Social Sciences, president of the Hungarian Network for Social Network Analysis, chair of the board of trustees at Home Start Hungary, and editor-in-chief of the European Journal of Mental Health.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment