If you speak to teachers at primary or elementary level, chances are that they know all their students’ names. When it comes to university level, though, we are likely to hear multiple reasons why teachers do not know their students’ names, such as “there are too many of them”, “we only meet once a week” or “they’re adults; they manage their own education”.

Over the 14 years of my teaching career thus far, I have always managed to remember my students’ names, on one condition, though: that lesson time amounts to more than one or two sessions during the term.

- What’s in a name? The importance of getting students’ names right

- Keeping dead names out of convocation

- Hidden stories in Indonesian names: you do not have a surname?

My personal record comes in at remembering 220 student names after two weekly lessons, although I may need to reboot my memory in the future if I do not see those students after the term ends. But during the term, at least, I know their names.

I mention this not to show off my memory prowess, but because there are educational objectives here. There are clear benefits to remembering students’ names. And I’d like to help you remember them, too.

The benefits

Firstly, calling a student by their name is a simple and effective way to get their attention. And there is scientific data to support this. In 2006, Dennis P. Carmody and Michael Lewis conducted a study on this utilising MRI. The findings revealed that several regions in the left hemisphere of the brain showed distinctive and greater functioning activation when one’s own name is used.

Second, a student’s name is the greatest connection to that individual’s identity and uniqueness and thus provides the greatest opportunity for building rapport. After all, their name was decided by those who love them, often using much thought and energy. In Asian societies, it is even common that geomancers are consulted to choose the most auspicious names.

Third, using students’ names is simply a courteous, respectful way of acknowledging them. It reflects well on the effort and professionalism of academics. If we are capable of attaining often tricky degrees, especially at a higher level, then the cognitive action of remembering students’ names feels possible given our brain power, especially if we try genuinely hard.

The steps

As I sat down to dissect how I manage to remember students’ names, I realised that there are only four steps towards this “feat”.

Step one: preparation

− Before your first lesson, look through the class list to get acquainted with your students’ names.

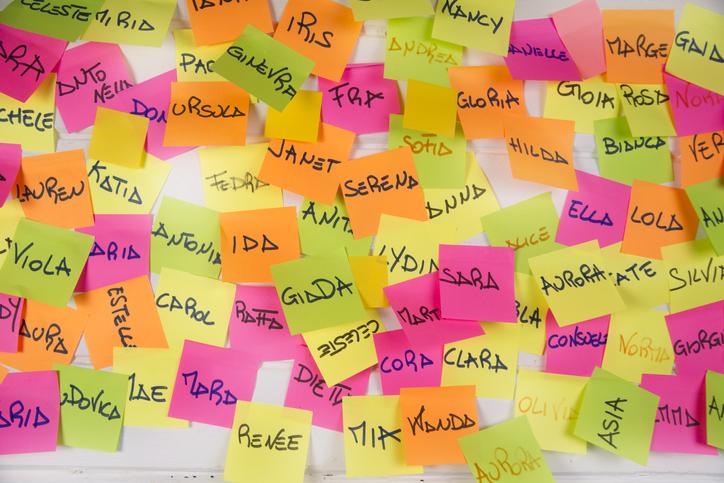

− Take note of any distinctive names, because they are easier to connect to the physical person/s.

Step two: repetition and association

− On the day of the first lesson, enter the classroom earlier if possible.

− As the students arrive, request their names one by one, and start to memorise them sequentially. For example, if the first student is John, repeat his name a couple of times in the mind. When Mary sits next to John, proceed to repeat in the head: “John, Mary”. Continue to do so for every four to five students who choose to sit near to one another.

− This method of remembering names in small clusters reflects what George A. Miller presented in 1956 as the concept of “chunking” – to help increase the brain’s short-term memory capacity.

− An alternative, but related, method is to use students’ names to form acronyms or abbreviations. For instance, if Tracy happens to be next to Evan and Nate, the trio can be conveniently remembered as “TEN” due to the first letters of their names. If the names do not constitute an easy acronym, any pattern may still be used, such as “MMRS” for a group that consists of Mark, Molly, Roy and Sophia.

− The intention of all these methods is to create a visual map of the names in the mind using digestible blocks of data.

Over the years, as my memory capability seems to degenerate (due to the self-diagnosed cause of ageing), I have proceeded to supplement that mind map with a quick sketch that acts as a backup tool, which you might find useful to create, too, especially if just starting out in this endeavour.

Step three: practice

− Once the lesson starts, use students’ names immediately and throughout.

− Where possible, strive to use all students’ names during your lesson. This practice helps to encode the data, as the names are now paired with voices, mannerisms and physical attributes. According to molecular biologist John Medina, this form of encoding is known as effortful processing. It involves all senses, is initiated intentionally and requires both deliberate attention and energy.

Step four: revision and retrieval

− Before the next lesson, review the physical map of names. The caveat here is that this is sometimes redundant because students change their seats.

− Even if this happens, though, the second lesson still starts off with an already partially populated database in the mind. So, it does become easier. Simply repeat the practice all over again.

This step reflects what neuroscientist Lisa Genova wrote in her book Remember – that to remember better, we have to repeatedly expose our brain to the newly acquired data and repeatedly retrieve it, too.

It is possible

Using the above-mentioned steps of reiterative learning and consolidating, I am able to retain students’ names in my memory by the end of the second weekly lesson.

Remember, as Dale Carnegie said: “A person’s name is, to that person, the sweetest, most important sound in any language.” That saying certainly applies in the classroom context, where remembering and using students’ names is one of the first and most useful steps towards building relationships with and educating them.

Ng Lee Keng is associate professor in the business, communication and design cluster at Singapore Institute of Technology.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment