Many universities are exploring how to prepare their students to live in a world increasingly affected by climate change. To do this, they are integrating sustainability into curricula by aligning teaching and research with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While this is an important first step, we would argue that sustainability education needs to go further than this in both depth and breadth.

We are a group of sustainability-focused academics who, over the past year, have been developing proposals for university-wide climate education at the University of East Anglia. This work has been undertaken as part of an informal network of staff and students who are motivated to embed sustainability more widely and more deeply within our university.

A number of other institutions are wrestling with the challenge of providing climate education. For example, the University of the West of England is reportedly the first UK university to offer a course to all staff and students. Falmouth University has financially supported students to create their own ecological citizenship course, and in Wales, a new higher education institute, Black Mountains College, has been established in the Brecon Beacons National Park in Wales. It offers interdisciplinary degree programmes that combine scientific knowledge, social theory and creative practice to equip students to become change-makers in a world that’s increasingly affected by climate change.

These institutions are pushing beyond the mainstream framings of sustainability and the SDGs, thinking about education in a more transformational way, and we found reviewing this work useful in thinking through ideas for our own institution.

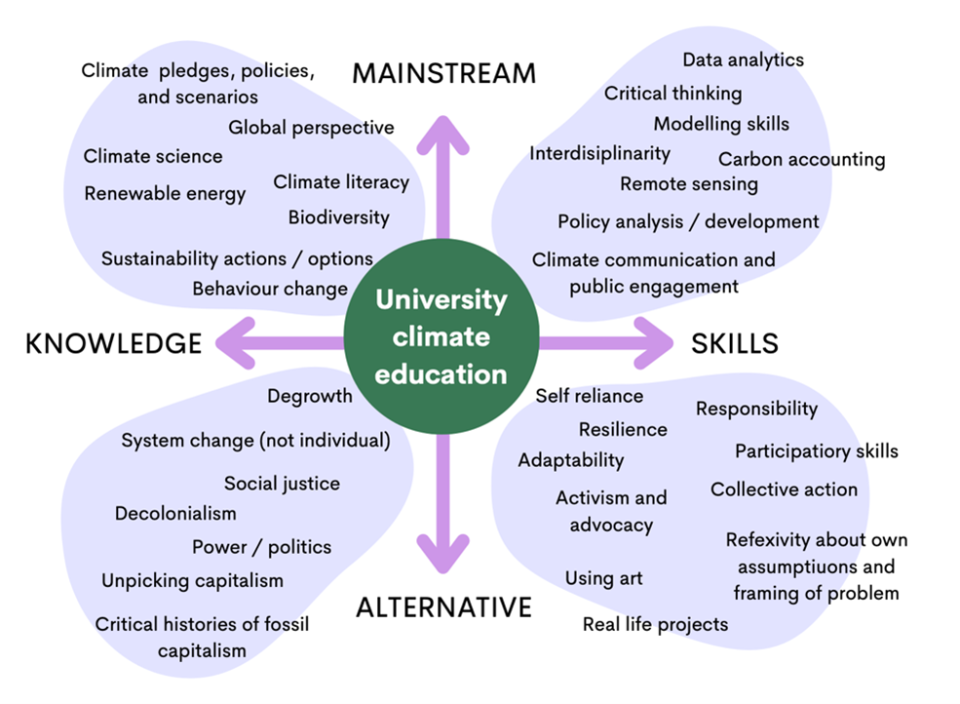

To make sense of the full breadth of possibility in climate education, we developed a framework based on two main axes around the approach and possible focus of climate education, ranging from approaches aligning with “mainstream” sustainability perspectives to “alternative”, more radical understandings, and from climate education that focuses on enhancing the knowledge of students to teaching that focuses on developing relevant skills (see figure 1).

The quadrants highlight that students need to understand the science of sustainability and its contested politics and values. Furthermore, as educators, we not only need to help them develop practical skills to contribute solutions, but to live fulfilling climate-informed lives. For us, a comprehensive sustainability education needs to engage with all four quadrants.

- Spotlight: A greener future for higher education

- Bridging the SDG awareness gap

- Embedding the SDGs into curricula via an interdisciplinary approach

Our proposals are based around the idea of engendering critical optimism in students. An explanation of the four quadrants is as follows:

Mainstream knowledge: this encompasses the dominant forms of knowledge and information about the climate crisis that are normally prioritised as part of climate education. It includes climate science, renewable energy, The Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. In effect, this informs the dominant, mainstream approach to sustainability that underpins government discourse and policy. It is a “green growth” vision that assumes, for example, that capitalism can be made sustainable.

Mainstream skills: these are the employability skills that our students will need to get jobs in the green economy. They include some specific disciplinary skills (especially those relevant to the environmental sciences) but a wide range of technical and transferable skills that can be applied in sustainability contexts.

Alternative knowledge: this is already taught in many universities but would currently be considered specialist knowledge that is taught within specific modules rather than as part of a wider climate education. However, we believe this is fundamental to a more rounded understanding of the climate and biodiversity crises. Relevant topics address the question of “How did we get here?” Alternative knowledge seeks to explore the contested nature of sustainability and the politics that surround it. This includes critiques of green growth and capitalism as well as exploring the links between colonialism and the climate crisis. We therefore suggest that students should be able to engage with critical social science perspectives to fully understand the crisis and to develop their own perspectives on how it should be navigated. This can include engagement with alternative positive visions of the future such as degrowth, where there is a primary focus on living within ecological limits rather than growing the economy. We should encourage students to critically assess different arguments and develop their own perspectives.

Alternative skills: these skills relate to supporting students to become empowered and resilient agents of positive change. Actively living within the climate crisis (rather than avoiding or ignoring it) is not easy. If we wish to learn this ourselves and support our students to join us on this journey, we need to talk about the tools required to navigate the difficult emotions such an acknowledgement can cause. We want to develop a sense of collective responsibility, preserve hope and nourish inner motivation with the goal of forming individual and societal resilience. Equipping students with tools and opportunities to build collective responsibility and individual resilience is essential.

Including certain forms of alternative knowledge and alternative skills within a climate curriculum for all students might make some university administrators and academics uneasy, not least in the context of the neoliberal university, which is based on the premise of capitalist growth. Yet we would argue that to omit such content would be to deprive students of the necessary tools to understand and navigate the current crisis. A decision to consciously avoid the controversies and more difficult aspects of sustainability is itself a political position that often favours the dominant power structures.

We are part of a wider movement of academics who believe that universities should be undertaking more comprehensive and rapid action to improve their own environmental sustainability across a range of areas including teaching. In doing so, universities can fulfil an important leadership role in the climate crisis and beyond. We believe that providing a comprehensive climate education for all university students is integral to this effort.

You can read the full education proposal here.

Noel Longhurst is associate professor in energy and climate change; Phedeas Stephanides is senior research associate; Franziska Hoerbst is a postgraduate researcher at the John Innes Centre; Hannah Hoechner is associate professor in education and global development; and Duncan Maguire is a lecturer in organisational behaviour, all from the University of East Anglia. Elliot Honeybun-Arnolda is a postdoctoral researcher in environmental STS at the Technical University of Munich.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment