Teaching sets a rhythm for education – a rhythm that students respond to consciously and unconsciously as they learn. This is an idea that has stayed with us since Victoria University (VU) implemented the block model in 2018.

We are not the first to use this insight, but we found it compelling as we comprehensively remade our learning and teaching model. The change from 12-week semesters to four-week blocks, from four units (subjects) at a time to one, from weekly lectures and tutorials to thrice-weekly workshops, and the adoption of thoroughly blended learning resources forced us to engage with students’ need for clear and reliable rhythms of study.

- Block teaching: what it is, how to do it and why

- Block mode of teaching in higher education: advantages and challenges

- How block teaching supports students from under-represented groups

This has many elements, of course. We have found it particularly valuable to focus on three.

1. A rhythm of the study calendar

The VU block model usually offers a unit of study as three class sessions per week for the first three weeks, then two classes in the final week. That allows all results to be complete by the final Friday of week four, so students can start their next block with the previous one all wrapped up. Before 2018, many of us did not believe that was possible; now we take it as given.

Workshops are three hours long for most subjects. They must be scheduled for the same hours each time we offer them, and they cannot run consecutively for more than two days at a time. Students each receive a personalised annual timetable for their classes at the start of each year.

These are the constants around which students can plan their studying lives – taking into account their on-campus time, sure, but also paid and voluntary work, family commitments, exercise and recreation. Together with engaging curricula and scaffolded assessment, these certainties have driven up class attendance across all our coursework degree programmes. Higher attendance is a powerful force for student retention and for the completion of assessment tasks, and we were intensely proud that first-year undergraduate attrition and fail rates both fell by more than 30 per cent when we introduced the block model.

2. A rhythm of assessment and feedback

A class group studying a subject over a semester or term traditionally completes assessment tasks of escalating consequence, which start several weeks after the subject has started. The assessment regimen will usually culminate in a large final task sometime after classes have finished.

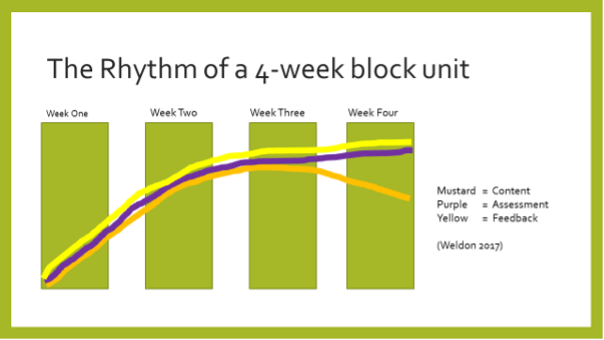

That sequence means students often do not get a chance to debrief with their teacher about their most important assessment piece, as this schematic by my colleague John Weldon depicts:

The teacher feedback that students receive on each assessment task will rarely arrive in the same week as they complete it; sometimes it will be more than a month later. As a result of the delay, focus falls on the fine details of work submitted – and focusing on the fine details often compounds the delay. Heavy marking workloads and low student engagement also characterise the situation.

There is no proof this conventional system works well. Only a few students are committed enough to read the detailed feedback on their work, handed down so long after they completed it. Because so much feedback is delivered after the semester, once the teacher-student relationship for a given class has ended, there is often little evidence to show the feedback has made an impression.

The evidence-led alternative is to say that frequent and scaffolded components of assessment, accompanied by rapid or even immediate feedback, are better at supporting learning. Emphasising fast and clear marking practices, using rubrics to ensure that teacher feedback is organised around the assessment criteria, is far more conducive to the formative learning that progressive assessment design seeks to deliver. Weldon’s next schematic shows VU’s preferred model of rapid and continuous assessment and feedback, within the intensive delivery of a four-week teaching block:

3. A rhythm of the workshop

Each workshop has its rhythm, and we actively design our lesson plans so they support student engagement, enabling the students to emerge as leaders of their own education.

It is easy for teachers and students alike to slide into assumptions that the activity in a workshop is predominantly or entirely a one-way affair, but such assumptions are toxic. They stifle precisely the strategic agency and critical thinking that higher education is supposed to encourage. Actively establishing a class rhythm that prioritises student activity and engagement is a powerful tool to recast these assumptions.

It is important to open every workshop with the students making the most of the active effort in the room (whether that room is physical or virtual). Otherwise, the starting behaviours will entrench expectations that students are passive. Class discussion characterised by a student-teacher talk time ratio of 2:1 or higher is one manifestation of this approach, relevant to some subjects; others will use “outdoor curriculum” (moving around) or industry-applied work to place students in the driving role rather than teachers.

Likewise, it is also valuable to close each workshop with the students making the most of the active effort. That way students’ lasting memories of each workshop are of the interaction and collaboration, not the sitting back and absorbing. It may mean setting the class a closing problem to explore interactively; it may mean referring assessment activities to small groups for planning, drafting and editing during class time; it may mean asking students to debrief on work or tests just completed.

By logical exclusion, the teacher-led content works best sandwiched in the middle of each workshop, occurring both before and after student-led work. Prepared slides sit most comfortably in this zone, as does in-class reading time or teacher-led discussions of the reading. Teacher-led content is most valuable when it supports student activity. Student engagement is the main driver of block learning.

Tom Clark is professor in First Year College and a researcher in the Institute for Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities at Victoria University, Melbourne.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment