For college students who are parents – that’s roughly a quarter of today’s college undergraduates – it’s neither their age nor their jobs that are the largest hurdle to acquiring the education and training they seek to move up in the world. It’s the enormous expense of caring for their children while they return to school.

A recent national report found that the median annual price for childcare for a single child in the US can range from about $5,000 (£4,125) for school-age home-based care in rural areas to more than $17,000 (£14,000) for centre-based care for infants in the nation’s largest metro areas. The US Department of Labor estimates that childcare consumes between 8 per cent and 19.3 per cent of median family income per child. Students who are parents are already much less likely than other students to finish college. And, with pandemic-related subsidies expected to expire in September, experts worry that even more families will find childcare to be unaffordable or unavailable.

- Read more: how to factor family into higher education

- What parents need to succeed in academia and how universities can help

- Twenty per cent of US undergraduates have children – we must do more to support them

Colleges and universities have long offered childcare to support their student-parents, and research has suggested that convenient childcare can increase retention and graduation rates. But for many institutions, on-campus childcare has run headlong into a thicket of expenses and regulations. It’s no wonder, then, that the number of colleges offering access to childcare has been declining for years.

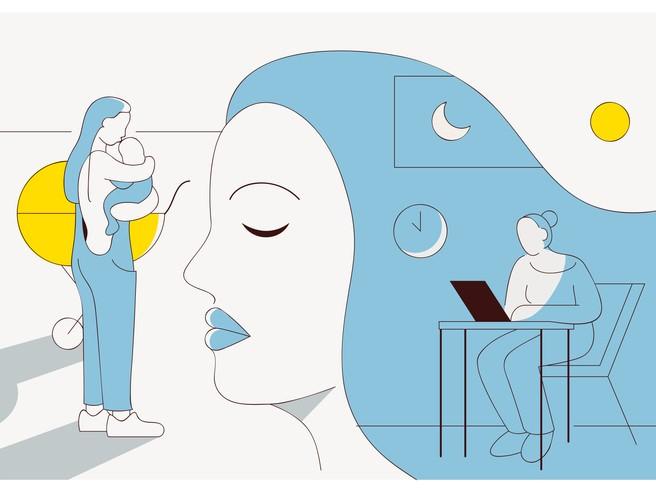

Adult students have complicated lives. Colleges must acknowledge that fact and strive to help parent-learners balance school, childcare and competing demands on their time. The need for childcare is especially critical in communities of colour, who will make up the majority of the US workforce by 2050. Here are three ways postsecondary can design programmes that meet them where they are with their childcare needs.

Institutions should create flexible schedules that respect learners’ time

For many student-parents, especially those who work, it’s inconvenient to be on campus three to five days each week. With available technology, it’s inefficient for many students to have to drive to campus for lectures. By offering didactic instruction in an asynchronous online format and requiring students to come to campus just two days each week for in-person lab-based instruction, institutions can make it easier for students to carve out time for school and reduce the number of hours their youngsters must spend in childcare. This approach ensures that only what needs to be done on campus is done on campus.

The College of Health Care Professions, where one of us works, is piloting a schedule that brings medical assisting students to campus only one day each week so they can practise drawing blood, taking vital signs and other hands-on skills. The college already offers two-day-a-week programmes that cut childcare needs, and reducing in-person class requirements to one day a week makes college a reality for those juggling jobs and those who live long distances from campus. Relieving the childcare burden can help reduce educational poverty in underserved communities.

Institutions should find partners in many places

Experiential learning – learning through projects, internships and off-campus programmes – is gaining popularity. Students preparing for medical professions must have clinical experience to earn their certificate or licence. It’s easy for institutions to arrange these opportunities with organisations close to campus. But institutions must be cognisant that many of their students – especially adult learners with families – often don’t live close to campus. The nearest clinical placement for the institution might be inconvenient for the learner, especially if their children have school or childcare close to their homes but far from campus or their externship site. Institutions should intentionally broaden their network of organisations for internships, externships and other clinical experiences. More opportunities for placements mean more opportunities for more learners and a greater potential for programme completion.

Institutions should provide learners with wraparound services

Colleges and universities traditionally provide academic and health and wellness support. But institutions should go beyond these obvious needs. Many students need help with transportation and food. Some learners need short-term child assistance during class sessions or required externships. A stipend that helps cover childcare expenses during an externship could be the boost that helps a learner complete a programme.

Institutions should be proactive with their support. Rather than waiting for students to ask for help, institutions must anticipate their needs. Students who miss class or fail to turn in assignments often need support, whether it’s academic or personal. Institutions must monitor student progress and work to solve challenges as they arise. If students can be retained, they can graduate.

Colleges and universities cannot solve the nation’s childcare crisis. But they can take steps so that the need to care for one’s children does not prevent someone from seeking and earning a valuable college credential. Removing the childcare barrier can be the difference between a student landing a good job and sitting on the sidelines during this economic boom.

Joanitt Montano is provost and vice-president of academics at the College of Health Care Professions, US.

Chike Aguh is a former chief innovation officer at the US Department of Labor and an adviser on the Project on Workforce at Harvard University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment