Rubrics comprise a critical part of assessment and evaluation in college courses. Regardless of course delivery format, rubrics are a tool to provide meaningful and measurable feedback to students. Rubrics help educators to define criteria by which to evaluate specific assignments, projects and other course completion standards. Communicating expectations to students via rubric scoring and feedback allows students to summarise critical components of standards for achievement before and after an assignment. When rubrics are presented alongside assignments, research shows that students use the rubrics as guidance and successful assignment completion.

For this guide, we will focus on the analytic rubric. An analytic rubric conveys levels of performance for different criteria that make up an assignment. Analytic rubrics compartmentalise the assignment criteria for independent evaluation, providing multidimensional and specific feedback to assess student performance on each of these focus areas.

- Resource collection: putting feedback at the heart of assessment

- A step-by-step guide to designing rubrics that will save hours of marking time

- Build effective rubrics in just five steps

Before designing an analytic rubric, teaching faculty need to be aware of essential rubric components alongside the evaluation criteria for each assignment. Here, I will discuss developing an analytical rubric by focusing on evaluation criteria, rating scales and task descriptors.

The first step to analytic rubric creation is to define the goal and purpose of the assignment that is being evaluated. Referring to course outcomes and the assignment’s alignment to specific outcomes is a good place to start. Designing an effective rubric ensures that the criteria and expectations are clearly defined and directly aligned with course outcomes.

Evaluation criteria: An excellent starting point is clearly defining essential skills or concepts that students should know or be able to do upon successful assignment completion. Instructors should define the complexity of knowledge needed to exhibit an aptitude for each criterion.

- Evaluation criteria will vary from assignment to assignment. For example, an individual student presentation may be broken into the following criteria: presentation organisation, subject knowledge, use of visual aids, mechanics, eye contact and presentation delivery. Whereas criteria for a student essay may be broken into criteria including opening thesis statement, relevance to the topic, subject knowledge, closure statement and mechanics.

- When choosing appropriate evaluation criteria, the instructor should consider the assignment’s primary focus (to ascertain topic knowledge, focus on presentation skills or design skills?) and its weight towards the final grade.

- Evaluation criteria should be stated concisely and serve to be viewed as an overall topic.

- Specific detail for each criterion level is outlined in the task descriptors (see below).

- It is critical for instructors to remember that each evaluation criteria may be weighted differently based on comparative importance towards the assignment goals. If the assignment’s primary goal is to improve students’ presentation skills, presentation-based evaluation criteria may be weighted more heavily than criteria for incorporating a written reflection.

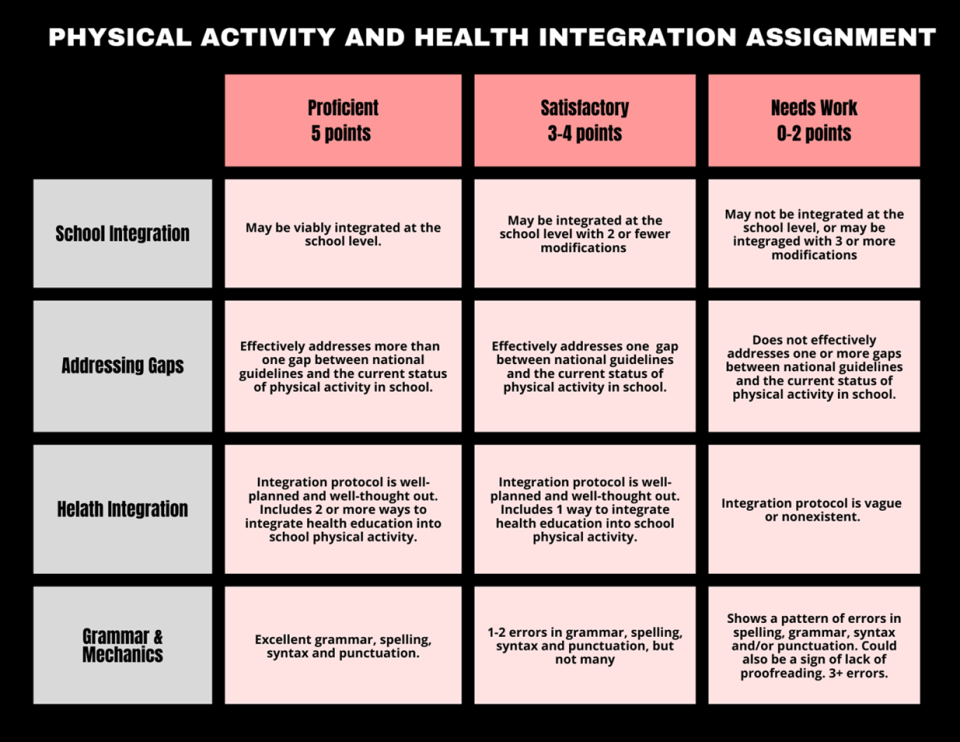

Figure 1 below shows the evaluation criteria in the boxes in the left-hand column in light grey: School Integration; Addressing Gaps; Health Integration; Grammar and Mechanics.

Rating scales: After the evaluation criteria are defined clearly, describe the rating scale to distinguish performance levels from one another for each evaluation criteria. When linked to a numerically graded assignment, it is common for instructors to use numerical rating scales.

- Consider limiting the rating scale to three to five criteria, with clear labels for each.

- Mindful word choice for rating scale labels is essential for instructors to convey clear expectations for success.

- It is critical to avoid overly negative or ambiguous labelling, and to incorporate labels that convey student levels of achievement. See the rating scales above titled proficient, satisfactory and needs work. Each scale conveys the level of student performance and the appropriate range of potential points tied to each.

- Rating scale point ranges will vary from assignment to assignment. See the figure above and note that the student must earn five points for proficient consideration.

- Rating scale point ranges may differ based on the assignment type and the number of evaluation criteria.

In Figure 1, the rating scales can be seen in the boxes in top row in pink: “Proficient (5 points), Satisfactory (3-4 points) and Needs Work (0-2 points).

Task descriptors: Task descriptors define achievement levels – what students must achieve or demonstrate for each evaluation criterion. Task descriptors should be conveyed in sentence form, vary by rating scale, and clearly outline expectations for achievement.

- Expectations for each task descriptor should be listed in detail, and each descriptor should be clearly differentiated from the descriptor in the level above or below.

- They should measure progress towards mastery of the evaluation criteria and be realistic and relevant.

- When creating task descriptors, consider the top-tier evaluation criteria first. It is beneficial to begin by defining the task descriptor for maximum points and then consider what components of that descriptor must be present or absent to fit into the lower rating scale categories.

- The instructor should consider clearly defined task descriptors criteria to minimise subjectivity while allowing students space to exhibit creativity and individuality.

In Figure 1, the task descriptors can be found in the light pink directly underneath the first row and to the right of the first column.

It is important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all way to design rubrics. Most importantly, it is critical to remember that when presented alongside an assignment, research shows that students tend to use rubrics as guidance towards successful assignment completion.

Jamie Gilbert Mikell is an assistant professor of kinesiology, health and physical education at Athens State University.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment