The pandemic is over. Not really of course, but most countries are ending their restrictions, and with a violent war taking place on Europe’s doorstep our priorities are suddenly very much elsewhere.

One of the very positive legacies of the past two years is that science and scientific research is probably more visible and publicly lauded than at any time since 1945 – partly because of its rapid response to the pandemic, but also for its potential to underpin economic prosperity and its role in addressing huge challenges such as climate change. Big budget increases for research are promised and politicians talk about Britain as a “science superpower”. Surely this all bodes well for public trust in the scientific consensus around climate change and support for ambitious carbon “net zero” targets in the UK and Europe?

Perhaps. But the lessons of the past two years are not all positive. Increased visibility for science and scientists has brought great public interest but also increased, entirely justifiably, scrutiny of the way science and scientists operate – their connections to power, their own priorities, the ways in which the scientific community is not as open and diverse as it could be, plus issues around bullying, harassment and scientific misconduct. It also brings an environment in which misinformation and misunderstanding about science can flourish if not challenged.

I’m therefore dismayed that the scientific communication toolkit used during the pandemic seems to have taken a definite step backwards in the ways we challenge this misinformation and misunderstanding.

- How to start an academic YouTube channel: tips from a psychology YouTuber

- Get your research out there: 7 strategies for high-impact science communication

- Enhance your research through public engagement and collaboration

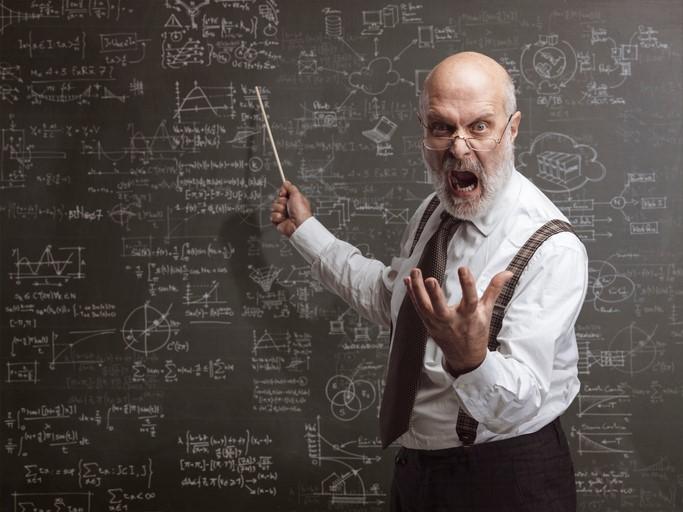

We spent decades trying to get away from the discredited “deficit model” of science communication, in which people’s presumed lack of awareness of science is simply the result of a lack of information: tell them more and they’ll agree. Rather than engaging with sceptics’ worries or concerns, it feels that we’re now right back in the bad old mode of scientific experts lecturing the public – about Covid, vaccines and lockdowns.

It’s as if we believe that in an emergency, we don’t have the luxury of engaging with people and we need to simply tell them what “science” says. We get frustrated when they don’t agree. We even cheer when they’re teargassed and locked up, whether in Rotterdam, Ottawa or closer to home. When did we all forget that we already know this approach doesn’t work?

It doesn’t work because it alienates a significant minority of the population. It plays right into the hands of those who, for their own motives of self-aggrandisement, set themselves up as leaders and critics of the establishment. Sure, we’ll never change those people’s beliefs – if they even have any – but we must try to win over those who are tempted to support them out of an entirely understandable desire to question what they are told by their “betters”.

It’s especially ironic that scientists – who pride themselves on challenging orthodoxy, on “taking nobody’s word for it” as the famous motto of the Royal Society proclaims – seem to have so little empathy with members of the public who question the view of experts. If we don’t stop and reflect, we will make these same mistakes around engagement with climate change and the behaviours needed to meet our net-zero targets, with potentially very serious implications. We will even end up as a potent recruitment tool for science deniers.

Now, of course, there really is a huge deficit in basic public understanding of science. But what’s at stake here isn’t really a layperson’s agreement with science they’re not qualified to assess. It’s agreement about the policy implications of science, and here the scientists don’t have a uniquely privileged status.

We often behave as if the science and the policy are the same thing. If you believe the science (and you must, we say, because it’s true!) then you must agree with the policy. But it’s quite possible to agree that climate change is real, that we must therefore dramatically reduce our CO2 emissions, but still disagree on the best way to do this. Should we invest in new nuclear power stations or not? Should we rely on carbon capture and storage technologies? How can we best deliver a nationwide shift in home heating?

When we act as if the science and the policy are the same, anyone who doesn’t like the policy just concludes that they don’t need to trust or believe in the science either. What we need to do is educate about the science and engage with the public on the policies.

How can we do this? Firstly, I would love to see the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy support a proper public engagement exercise around the UK’s net zero goals – not in the spirit of a publicity drive but to actively explore public knowledge of the underlying science and attitudes towards the interventions needed.

And there’s lots we can do as individual scientists too. First and foremost is to engage with the public – to get out there and have a conversation. And we need to do so with unexpected groups – it’s lots of fun talking to those who are already interested in science, but it’s probably more useful to speak at a miners’ social club than a science club.

Let’s aim first to educate about the science of climate change and then use this to stimulate a discussion around the ways society needs to react. Let’s resist the urge to preach and remember that people can agree that this is a pressing issue while still questioning some of the government’s plans – doing so doesn’t make them idiots, Putin shills or flat-earthers. Let’s also remember that this is a long game, and one interaction, talk or interview won’t change anyone’s mind – but hopefully it can start a process.

It’s always easier and more of an ego boost to speak from a position of authority and expertise and demand compliance from the “ignorant”. It is hard work to listen, from a position of humility, understand opposing priorities and work for agreement. But that’s what we need to do. Rhetoric about a climate emergency really doesn’t help, because it implies we don’t have time to engage. In fact we don’t have time to not engage. Science communication knows this already; we just need to forget the Covid mistakes, rediscover our tools and put them to use.

John Womersley is visiting professor of physics at the University of Oxford. He was previously chief executive of the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment