Mistakes and errors in writing can confuse any reader, but those same mistakes also impact a reader’s confidence in the writer. For example, a 2019 study found that when a group of average readers were asked to evaluate a potential employee’s written application materials, grammatical errors implied that the writer was less competent and less intelligent than applicants with error-free submissions.

Teachers of writing know that errors don’t necessarily equate to either of these abilities. Still, after hours of reading student papers and emails, one becomes worn wading through errors in discussion boards and the like.

Teachers of all subjects, it is our job to remind students that perception implies reality. Errors don’t imply a good reality, so let’s collaborate to get rid of them. But how do online instructors show students that (a) sentence-level errors matter, and (b) we can grow beyond them?

- Focused freewriting is the cure for students’ writer’s block

- If peer feedback was good enough for the Brontë sisters, it’s good enough for us

- Creative writing to hone critical thinking

The process must start at the beginning of a class and remain a sustained effort all term. The resources provided by our institutions and the bountiful supply of free online resources can bolster our efforts to help students see the tangible value in the time-consuming proofreading process.

Leveraging those resources can start on the first day of class and span all areas of your classroom, from discussion areas to private grading spaces.

Consider this three-step process for integrating those proofreading resources; practise the acronym RIG:

1. Remind students to proofread carefully

2. Inform them of your institution’s writing support resources

3. Guide them to online writing resources of your choice to learn proofreading methods, such as this great video from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s writing centre.

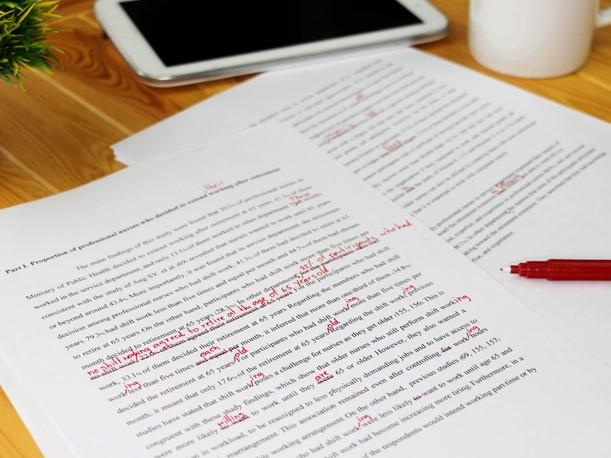

There are many methods for demonstrating the negative power of sentence-level grammar errors to students, but this suggestion sends a vivid picture that can be particularly important for visual learners:

On the first day of class, in an announcement section or other public section of the class, such as a shared email chain, craft a message that is full of errors. For example: Ples red this mesige for claretee. (The proper spelling for this message is: Please read this message for clarity.)

On the second day of class, send a second message, this time explaining the types of writing support available in your classroom. To help craft that message, consider that most online learning institutions have one or more of these three forms of writing support:

1. The teacher gives comments on a paper and personally teaches each skill necessary − a difficult method to follow when there are many students in each class.

2. The teacher gives comments on a paper with instructions. The student applies that feedback with a writing tutor provided by the institution. At my institution, Colorado State University Global, we have in-house tutors who give feedback based on teacher comments. Other institutions might contract writing tutors, like Smarthinking, for example. If writing tutors are available, you may choose to offer the link to those tutors and guidelines for how students can take your feedback to them for further writing instruction on proofreading and avoiding grammatical errors.

3. Finally, if there is no writing tutor system available at your institution, you might create your own tutorials by guiding students to online resources for common errors you notice in their writing. For example, you might choose to offer a list of proofreading resources like the one provided above by UNC-Chapel Hill, or you might choose, instead, to provide a virtual session to teach the class how to search for online writing resources that suit each writer’s particular learning style. The key idea is to share the resources early and often in group areas and in individual feedback so that students know you value the hard work required to proofread for grammar and sentence-level errors.

Once you have your messaging about writing support in place, examine your grading practices for rewarding proofreading. If you work in an online setting that allows you to determine your own grading criteria and rubrics, you can further underscore the value of proofreading by grading more than one draft of a student’s writing.

For example, you might award one grade for a rough draft of a paper in which students are asked to simply draft or outline to get ideas in order. For this task, note that no deductions will be made for sentence-level errors. Instead, you will grade and offer feedback only on the ideas.

For the next iteration of the paper, remind students that you will be grading for content and proofreading. In assignments and shared spaces, remind students how to take control of their own revision process, using the tools or tutors you utilise in the class. Remind them, too, that the rubric will reflect a hefty number of points for the time they devote to the proofreading process.

Rubric points evidence the value of the revision process. Students do the work, they get the numeric reward and everyone wins. You read better writing, and the students grow as communicators by realising their own personal power to correct mistakes and to create a perception that mirrors their best reality.

Teaching students to leverage online writing tools on their own initiates permanent, personal pathways for ever-improving communication skills in formal education settings, the workplace and beyond.

Stone Meredith teaches college-level composition, literature and philosophy courses at Colorado State University Global. She is actively involved with the university’s Rocky Mountain College English Association.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment