As we set about bringing change in various institutions, many of us have been warned against “stepping on toes” during what were ostensibly encouraging conversations. It’s a perplexing warning at first – perhaps incongruous, perhaps slightly unsettling – but ultimately it’s the kind that drains energy and ambition. Whose toes might you be about to step on and by doing what? Will it be clear if it’s about to happen or will you only know in retrospect? Is there another way to do things that doesn’t endanger any toes?

The feeling that this all engenders, and our near-ubiquitous experience of it, prompts us to feel it is a sentiment worth unpacking. “Don’t step on anyone’s toes” signals many things about universities. It reveals something of the lived reality of working in organisations as large and complex as these, places in which accountability and responsibility are often distributed, sometimes abrogated, and might not map neatly on to any organisational chart. Most universities are decades, if not centuries old. They carry their history with them in legacy organisational structures, the role definitions (and titles), as well as mindsets, skill sets and ways of working.

To get things done in universities, do we need to embrace conflict? Should we not worry about stepping on toes? Discussing a not dissimilar organisation, the UK civil service, Andrew Greenway, Ben Terrett, Mike Bracken and Tom Loosemore note in their 2021 book, Digital Transformation at Scale, that “the major determinant of long-term personal success” in the civil service is the ability to “keep your colleagues close” and therefore “if there is an explicit argument or disagreement, that is a problem in and of itself”.

“Successful digital leaders need to embrace a degree of conflict – as well as the ability to collaborate – in order to unblock institutional issues that prevent change from happening,” they write. “In doing so, they are effectively pencilling their resignation letters from day 1 within a culture that places little value in bringing issues to a head, nor gives incentives to do so.”

- How to turn an average collaboration into a dream team

- Advice for effective cross-team collaboration for research

- Five tips for building healthy academic collaborations

Unlike civil servants, many academics relish a degree of intellectual conflict, and yet universities seem ill-equipped to productively handle conflict. Some people want to argue each point from first principles and the argument can seem like the end-point in itself – not a stage in coming up with a better way of doing things. Arguably, a persistent distaste for formal management leads to the neglect of structures and skills that mediate conflict and some pretty shoddy practices passing as management.

Universities are not dissimilar to many organisations in that people who end up making decisions – or interpreting what decisions will mean in practice – have been successful within the status quo. What might be unusual about universities is that those people may have been successful as researchers rather than managers: building exquisitely detailed expertise and insight about a given topic, but at the expense of a diverse breadth of experience and responsibilities. Moreover, we would argue that one of the consequences of the lack of clarity about responsibility and accountability is the persistence of organisational cultures that cling to indefensible hierarchies such as those between academic and professional service staff and research and education work. While universities would no doubt benefit if they were to evolve to be organisations that could better manage conflict, we suggest that, in the here and now, we must develop strategies for collaboration.

Understanding that collaboration needs to be proactively designed and nurtured is, we think, an idea that makes a difference for digital transformation. Collaboration requires skills such as the ability to work with people who have different expertise and experience, and the ability to accept and process creative tensions as a group (this is partly about trust and relatability, which may be at an all-time low in HE). These skills will be developed through practice and will benefit from good facilitation.

There are many possible approaches, but in this blog we highlight prototyping as a tool to support collaboration.

How prototyping can be used to improve processes

A prototype is a low-fidelity rendition of a possible solution. It acts as a boundary object between different expertise and different needs, enabling people to collectively deepen their shared understanding. Prototypes externalise ideas in ways that facilitate conversations about possible solutions and allow people to play with and iterate ideas in a low-stakes and psychologically safe environment.

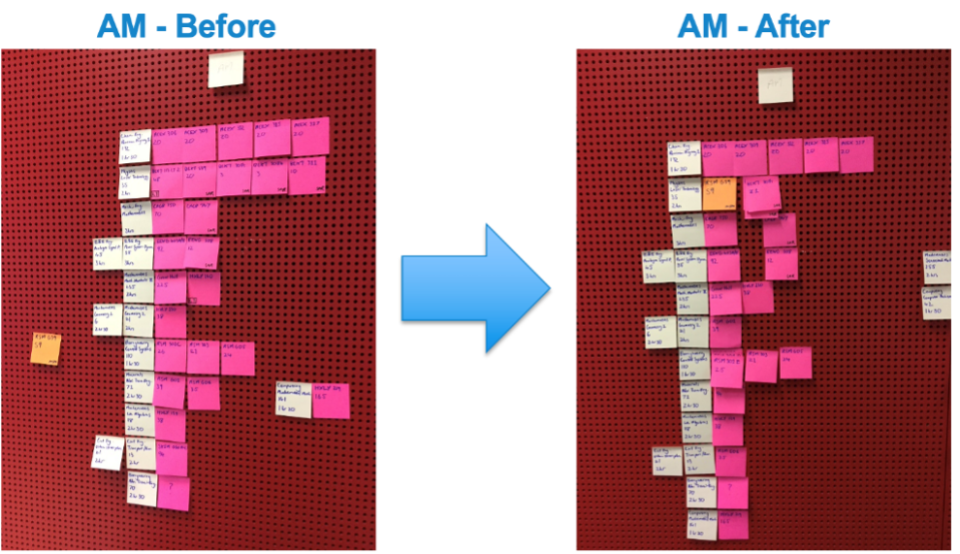

As an example, Imperial College London used prototyping to improve timetabling of exams at a time when it was felt there weren’t enough places in exam halls. While the status quo of devolved responsibility was familiar and had department confidence, it also meant the timetable was built as a collection of locally written timetables. Some students would therefore sit exams in halls that weren’t full, while others would be in rooms that no one would choose to sit an exam in. The cross-department working group wrote a proposed re-rooming protocol with volunteers. They then modelled the approach using a visual prototype to illustrate how it would work and the change in outcomes.

Participation in the prototyping process gave timetablers and department academic leaders the confidence to pilot re-rooming at scale for the next examination cycle. The net result was that more than 8,200 students sat examination papers in better conditions than they otherwise would have, with the work of the extended team recognised by university awards. These results catalysed a stream of ongoing service enhancements, including development of digital approaches for collecting requirements and modelling timetables.

What does it mean in practice?

Digital transformation requires us to build organisations that support productive collaboration. Here are ways we suggest we might begin to do that:

- If you hear someone telling you not to step on anyone’s toes, pay attention. If you notice in the moment, ask them to say a little bit more about that: what kind of thing are they thinking about? Has that happened in the past? What do they think are the dangers of “stepping on toes”? And what are the costs of working with that intention?

- Allow time in project schedules and processes to build relationships and to agree ways of working.

- Actively create an inclusive culture in which people can challenge hierarchies without fear of repercussions.

- Use facilitation tools to invite diversity of expertise and perspective into the process.

- Use prototypes as a way to allow people to draw on their own experience and expertise to assess possibilities across specialisms. The This is Service Design Doing methods library is a great place to explore this approach.

Sarah Dyer is an associate dean for teaching and learning at the University of Manchester. Lisa Harris is director of digital learning at University of Exeter Business School. Craig Walker is a director of HEdway Group.

Sarah Dyer, Craig Walker and Lisa Harris will be among the speakers at Digital Universities UK on 16-18 April at the University of Exeter. Their session is “Ideas that make a real difference”.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment